Luhya people

The Luhya (also known as Abaluyia or Luyia) are a group of 20 Bantu clans in Kenya that have a common origin and have been politically united since 11th BC . They number 9,823,842 people according to the 2021 estimate, being about 16% of Kenya’s total population of 55 million, and are the largest ethnic group in Kenya.

Luhya refers to both the 20 Luhya Clans and their respective languages collectively called Luhya languages. There are 20 (and by other accounts, 21, when the Suba are included) clans that make up the Luhya. Each has a distinct dialect. The word Luhya or Luyia in some of the dialects means “the north”, and Abaluhya (Abaluyia) thus means “people from the north”. Other translations are “those of the same hearth.”

The seventeen clans are the Bukusu (Aba-Bukusu), Idakho (Av-Idakho), Isukha (Av-Isukha), Kabras (Aba-Kabras), Khayo (Aba-Khayo), Kisa (Aba-Kisa), Marachi (Aba-Marachi), Maragoli (Aba-Logoli), Marama (Aba-Marama),Aba-luhya luo in Siaya, Nyala (Aba-Nyala), Nyole (Aba-Nyole), Samia (Aba-Samia), Tachoni (Aba-Tachoni), Tiriki (Aba-Tiriki), Tsotso (Abatsotso), Wanga (Aba-Wanga), and Batura (Abatura). They are closely related to the Masaba (or Gisu), whose language is mutually intelligible with Luhya. The Bukusu and the Maragoli are the two largest Luhya clans.

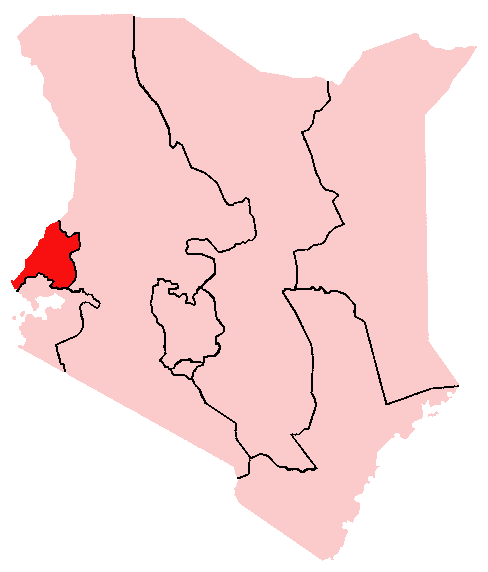

The principal traditional settlement area of the Luhya is in what was formerly the Western province and Nyanza province of Kenya. A substantial number of them permanently settled in the Kitale and Kapsabet areas of the former Rift Valley province. Western Kenya is one of the most densely populated parts of Kenya. Migration to their present Luhyaland (a term of endearment referring to the Luhya’s primary place of settlement in Kenya after the Bantu expansion) dates back to as early as the 7 BC.

Immigrants into present-day Luhyaland trace their ancestry with several Bantu groups and Cushitic groups, as well as peoples like the Kalenjin, Luo, and Maasai. By 1850, migration into Luhyaland was largely complete, and only minor internal movements occurred after that due to disease, droughts, domestic conflicts and the effects of British colonialism.

Origins and history

Overview

Anthropologists believe that the progenitors of the Luhya were part of the great Bantu expansion out of Central Africa around 1000 BC. In sharp contrast with anthropologists, the Maragoli oral history states that they migrated into what is now Kenya, from Misri (Arab word for Egypt). However, the majority of the other Luhya tribes are mostly from present day Uganda and are diverse in origin.

The most powerful centralized kingdom in what is now Kenya was founded by the Wanga.

The Wanga would sometimes hire Maasai and Kalenjin mercenaries to fight for them. The Wanga incorporated most of the Luhya tribes as well as territories to the east, southeast, west and southwest occupied by the Luo, Kipsigis, Nandi, and Masai.

Pre-colonial period

Before the advent of colonialism, the Luhya, just as most other ethnic groups in Africa, defined their boundaries based on occupation of territory by a community of peoples with similar language, cultural traditions or under leadership of a particular ruler or king.

Their territory neighboured the Baganda, Basoga and Bagisu of present-day Uganda, and the Luo, Teso, and Nandi of present-day Kenya. The territory occupied by the Bantu around Lake Victoria and to the north of Lake Victoria was known as Kavirondo. When the British came into the area, they coined the term Bantu Kavirondo to refer to the Luhya and other Bantu communities in the area while Nilotic Kavirondo was used to refer to the AbaLuo.

On the onset of colonialism in Kenya, the Wanga were ruled by Nabongo Mumia. The Wanga kingdom was and is a derivative of the Baganda. It was the most powerful and centralized kingdom in the region. Other leaders among the Luhya were known as Baami (singular Mwami), a title translating to ‘Kings’ or ‘Lords.’

The British explorer Henry Morton Stanley made a voyage around Lake Victoria, and Joseph Thomson, the Scottish geologist, passed through Luhya territory around 1883. Thomson met Nabongo Mumia and influenced British relations with the Wanga Kingdom in the region. The construction of the Kenya-Uganda railway beginning from 1898 further opened opportunities for European interaction with the Luhya and other communities in the western part of Kenya. Nabongo Mumia’s dominion extended to other Luhya subgroups such as the Kabras and the Tsotso.

In the late 1800s, when European nations began their Scramble for Africa, they mapped African boundaries to suit their interests in the continent. With the lion’s share of colonies going to the British, in 1895, the region of East Africa was declared to be a British Protectorate. It was further divided into British East Africa, (present-day Kenya) and the Uganda Protectorate (present-day Uganda).

As all the land in Kenya, west of Naivasha was mapped within the Uganda Protectorate, the Luhya people and other Kenyan communities were included in the Ugandan territory. In 1902, the boundaries were remapped and the Luhya peoples including the Wanga kingdom and their neighbouring communities which were on the eastern part of Uganda, were annexed to Kenya.

Colonial period

The first European the Luhya had contact with was probably Henry Morton Stanley as he voyaged around Lake Victoria. In 1883, Joseph Thomson was the first European known to pass through Luhya territory on foot, and was influential in opening the region to Europeans after he met with King Mumia of the Wanga Kingdom.

The Wanga Kingdom was very similar to the Baganda kingdom and other monarchies in Uganda, a unique form of government among the Luhya. Mumia was the last sovereign king of the Wanga, and because of ethnocentric British beliefs, was called a chief.

The Bukusu strongly resisted British incursions into their territory in the 1890s. In 1895, they fought the British from a stronghold near Bungoma on the lower slopes of Mount Elgon called “Chetambe’s Fort”. The British had machine guns and massacred over a hundred Bukusu warriors in the stronghold, who were armed with spears, hide shields, bows and quivers of arrows.

In the 1940s and 1950s the Bukusu resisted the British under the leadership of Elijah Masinde, a religious sect leader and prophet who demanded the return of their lands. Masinde was imprisoned during the Mau Mau rebellion in the 1950s, but was released to his home area at independence in 1963.

The Kabras and the Wanga collaborated peacefully with the British. Most Luhyas from the Kabras subgroup joined the colonial-era police forces. Nabongo Mumia, was forced to sign treaties with the British after being defeated, this allowed the colonial authorities to subject his people to British rule.

Significant numbers of the Luhya fought for the British in the Second World War, many as volunteers in the Kenya African Rifles (KAR). As with many African societies, the Luhya also named their children after significant events. Consequently, many Luhya people born around the time of the Second World War were named “Keyah”, a transliteration of “KAR”, the acronym for the King’s African Rifles.

Other famous chiefs during the colonial time included Ndombi wa Namusia, Sudi Namachanja, Namutala and Ongoma Laurende.

1. The Bukusu speak Lubukusu and occupy Bungoma and Mount Elgon districts. The clans of the Bukusu include the Bamutilu, Babuya, Batura, Bamalaba, Bamwale, Bakikayi, Basirikwa, Baechale, Baechalo, Bakibeti, Bakhisa, Bamwayi Bamwaya, Bang’oma, Basakali, Bakiabi, Baliuli, Bamuki, Bakhona, Bakoi, Bameme, Basombi, Bakwangwa, Babutu (descendants of Mubutu also found in Congo), Bakhoone, Baengele (originally Banyala), Balonja, Batukwika, Baboya, Baala, Balako, Basaba, Babuya, Barefu, Bamusomi, Batecho, Baafu, Babichachi, Bamula, Balunda, Babulo, Bafumo, Bayemba, Baemba, Bayaya, Baleyi, Baembo, Bamukongi, Babeti, Baunga, Bakuta, Balisa, Balukulu, Balwonja, Bamalicha, Bamukoya, Bamuna, Bamutiru, Bayonga, Bamang’ali, Basefu, Basekese, Basenya, Basime, Basimisi, Basibanjo, Basonge, Batakhwe, Batecho, Bachemayi, Bachemwile, Bauma, Baumbu, Bakhoma, Bakhonjo, Bakhwami, Bakhulaluwa, Baundo, Bachemuluku, Bafisi, Bakobolo, Bamatiri, Bamakhuli, Bameywa, Bahongo, Basamo, Basang’alo, Basianaga, Basioya, Bachambayi, Bangachi, Babiya, Baande, Bakhone, Bakimwei, Batilu, Bakhurarwa, Bakamukong’i, Baluleti, Babasaba, Bakikai, Bhakitang’a, Bhatemlani, Bhasakha, Bhatasama, Bhakiyabi, Banywaka, Banyangali, etc. For a complete list of Bukusu clans see Shadrack Amakoye Bulimo’s new book Luyia Nation: Origins, Clans and Taboos ISBN 978-1-4669-7837-9

2. The Samia speak Lusamia and occupy Southern Region of Busia District (Busia county), Kenya. The clans of the Samia of include the Abatabona, Abadongo, Abakhino, Abakhulo, Abakangala, Abasonga, Ababukaki, Ababuri, Abalala, Abanyiremi, Abakweri, Abajabi, Abakhoba, Abakhwi, Abadulu,

3. The Khayo speak Lukhayo and occupy Nambale District and Matayos Division of Busia County, Kenya. Khayo clans include the Abaguuri, Abasota, Abakhabi.

4. The Marachi speak Lumarachi and occupy Butula District in Busia county. Marachi clans include Ababere, Abafofoyo, Abamuchama, Abatula, Abamurono, Abang’ayo, Ababule, Abamulembo, Abatelia, Abapwati, Abasumia, Abarano, Abasimalwa, Abakwera, Abamutu, Abamalele, Abakolwe, Ababonwe, Abamucheka, Abaliba, Ababirang’u, Abakolwe, Abade. Abasubo. The name Marachi is derived from Ng’ono Mwami’s father who was called Marachi son of Musebe, the son of Sirikwa.So all the Marachi clans owed their allegiance to Ng’ono Mwami from whose lineage of Ababere clan they were founded. The name Marachi was given further impetus by the war-like lifestyle of the descendants of Ng’ono who ruthlessly fought off the Luo expansion of the Jok Omollo a Nilotic group that sought to control the Nzoia and Sio Rivers in the area and the fishing grounds around the gulf of Erukala and Ebusijo-modern Port Victoria and Sio Port respectively.

5. The Nyala speak Lunyala and occupy Busia District. Other Nyala (Abanyala ba Kakamega) occupy the north western part of Kakamega District. The Banyala of Kakamega are said to have migrated from Busia with a leader known as Mukhamba. They speak the same dialect as the Banyala of Busia, save for minor differences in pronunciation. The Abanyala ba Kakamega are also known as Abanyala ba Ndombi. They reside in Navakholo Division North of Kakamega forest. Their one-time powerful colonial chief was Ndombi wa Namusia. Chief Ndombi was succeeded by his son, Andrea.

Andrea was succeeded by Paulo Udoto, Mukopi, Wanjala, Barasa Ongeti, Matayo Oyalo and Muterwa in that order.

The clans of the Banyala include Abahafu, Ababenge, Abachimba, Abadavani, Abaengere, Abakangala, Abakhubichi, Abakoye, Abakwangwachi, Abalanda, Abalecha, Abalindo, Abamani, Abalindavyoki, Abamisoho, Abamuchuu, Abamugi, Abamulembo, Abasinyama, Abamwaya, Abanyekera, Abaokho, Abasaacha, Abasakwa, Abasaya, Abasenya, Abasia, Abasiloli, Abasonge (also found among Kabras), Abasumba, Abasuu, Abatecho (also found among Bukusu), Abaucha, Abauma, Abaumwo, Abacharia, Abayaya, Abayirifuma (also found among Tachoni), Abayisa, Abayundo and Abasiondo, Abachende.

The Banyala do not intermarry with someone from the same clan.

6. The Kabras speak Lukabarasi and occupy the northern part of Kakamega district. The Kabras were originally Banyala. They reside principally in Malava, in Kabras Division of Kakamega district. The Kabras (or Kabarasi, Kavalasi and Kabalasi) are sandwiched by the Isukha, Banyala and the Tachoni.

The name “Kabras” comes from Avalasi which means ‘Warriors’ or ‘Mighty Hunters.’ They were fierce warriors who fought with the neighbouring Nandi for cattle and were known to be fearless. This explains why they are generally fewer in number compared to other Luhya tribes such as the Maragoli and Bukusu.

They claim to be descendants of Nangwiro associated with the Biblical Nimrod. The Kabras dialect sounds like the Tachoni dialect. Kabras clans include the Abamutama, Basonje, Abakhusia, Bamachina, Abashu, Abamutsembi, Baluu, Batobo, Bachetsi and Bamakangala. They were named after the heads of the families.

The Kabras were under the rulership of Nabongo Mumia of the Wanga and were represented by an elder in his Council of Elders. The last known elder was Soita Libukana Samaramarami of Lwichi village, Central Kabras, near Chegulo market. When the Quaker missionaries spread to Kabras they established the Friends Church (Quakers) through a missionary by the name of Arthur Chilson, who had started the church in Kaimosi, in Tiriki. He earned a local name, Shikanga, and his children learned to speak Kabras as they lived and interacted with the local children.

7. The Tsotso speak Olutsotso and occupy the western part of Kakamega district. Tsotso clans include the Abangonya, Abashisiru, Abamweche, Abashibo,

8. The Idakho speak Lwidakho and occupy the southern part of Kakamega district. Their clans include the Abashimuli, Abashikulu, Abamasaba, Abashiangala, Abamusali, Abangolori, Abamahani, Abamuhali.

9. The Isukha speak Lwisukha and occupy the eastern part of Kakamega district. Isukha clans include the Abarimbuli, Abasaka- Ia, Abamakhaya, Abitsende, Abamironje, Abayokho, Abakusi, Abamahalia, Abimalia, Abasuiwa, Abatsunga, Abichina, Abashilukha, Bakhumbwa, Baruli, Abatura, Abashimutu, Abashitaho, Abakhulunya, Abasiritsa, Abakhaywa, Abasaiwa, Abakhonyi, Abatecheri, Abayonga, Abakondi, Abaterema, and Abasikhobu.

10. The Maragoli speak Lulogooli and occupy Vihiga district. Maragoli clans include Avamumbaya, Avamuzuzu, Avasaali, Avakizungu, Avavurugi, Avakirima, Avamaabi, Avanoondi, Avalogovo, Avagonda, Avamutembe, Avasweta, Avamageza, Avagizenbwa, Avaliero, Avasaniaga, Avakebembe, Avayonga, Avagamuguywa, Avasaki, Avamasingira, Avamaseero, Avasanga, Avagitsunda.

11. The Nyole speak Olunyole and occupy Bunyore in Vihiga district. Nyole clans include Abakanga, Abayangu, Abasiekwe, Abatongoi, Abasikhale, Aberranyi, Abasakami, Abamuli, Abasubi (Abasyubi), Abasiralo, Abalonga, Abasiratsi. Abamang’ali, Abanangwe, Abasiloli, Ab’bayi, Abakhaya, Abamukunzi and Abamutete.

12. The Tiriki speak Ludiliji and occupy Tiriki in Vihiga district. Tiriki clans include Balukhoba, Bajisinde, Bam’mbo, Bashisungu, Bamabi, Bamiluha, Balukhombe, Badura, Bamuli, Barimuli, Baguga, Basianiga and Basuba.

13. The Wanga speak Oluwanga and occupy Mumias and Matungu Districts. The 22 Wanga clans are Abashitsetse, Abakolwe, Abaleka, Abachero, Abashikawa, Abamurono, Abashieni, Abamwima, Abamuniafu, Abambatsa, Abashibe, Ababere, Abamwende, Abakhami, Abakulubi, Abang’ale, Ababonwe, Abatsoye, Abalibo, Abang’ayo, Ababule and Abamulembwa.

14. The Marama speak Lumarama and occupy Butere district. Marama clans include Abamukhula, Abatere, Abashirotsa, Abatsotse, Aberecheya, Abamumbia, Abakhuli, Abakokho, Abakara, Abamatundu, Abamani, Abashieni, Abanyukhu, Abashikalie, Abashitsaha, Abacheya, etc.

15. The Kisa speak Olushisa and occupy Khwisero district. Kisa clans include Ababoli, Abakambuli, Abachero, abalakayi, Abakhobole, Abakwabi, Abamurono, Abamanyulia, Abaruli, Abashirandu, Abamatundu, Abashirotsa, Abalukulu etc.

16. The Tachoni speak Lutachoni and occupy Lugari, Bungoma and Malava districts. Tachoni clans include Abachambai, Abamarakalu, Abasang’alo, Abangachi, Abasioya, Abaviya, Abatecho, Abaengele. The Saniaga clan found among the Maragoli in Kenya and the Saniak in Tanzania are said to have originally been Tachoni.

Other clans said to have been Tachoni are the Bangachi found among Bagisu of Uganda, and Balugulu, also found in Uganda and the Bailifuma, found among the Banyala.

Although Trans Nzoia is in the Rift Valley province, substantial Luhya populations have settled in the Kitale area.

Population and politics

In Kenyan politics, the Luhya population, commonly referred to as the Luhya vote in an election year, was usually a deciding factor of the outcome of an election. The community was known to unite and vote as a block, usually for a specific political candidate without division of mind and regardless of political differences. However, since the March 2013 general elections, this was proved wrong. They are now known to accept different ideologies. Politicians scramble for the Luhya vote since it is the most democratic voter in Kenya.

Given their high population numbers, a political candidate who enjoys Luhya support is almost always poised to win the country’s general elections, barring incidents of fraud. The community is thereafter “rewarded” politically, by one of their own being appointed vice president or to a high-profile political office by the winning candidate.

In the 2002 general elections of Kenya, the Luhya proved this point when outgoing president Daniel Arap Moi unexpectedly appointed Musalia Mudavadi as Vice president in an attempt to lure Luhyas to vote for Uhuru Kenyatta, his choice of successor with Musalia as running mate. The Luhyas remained adamant in their support for the opposition then led by Mwai Kibaki who also had a Luhya, Michael Kijana Wamalwa as running mate.

The Luhyas dealt a severe blow to Moi’s candidate by voting en masse for Kibaki who thereafter won the election with Wamalwa as his vice president. Of the eleven vice presidents of Kenya since independence, three have been Luhyas.

Others who have held high-profile political offices include, Musalia Mudavadi, current deputy Prime Minister formerly 7th Vice President (Sept. 2002 – Dec 2002), Michael Wamalwa Kijana, 8th Vice President of Kenya (January 2003 – August 2003, Moody Awori, 9th Vice President of Kenya (September 2003 – January 2008), Amos Wako, longest-serving Attorney General of Kenya – 19 years in office, Kenneth Marende, Speaker of the National Assembly and Zachaias Chesoni, late former Chief Justice of Kenya.

Culture

Luhya culture is comparable to most Bantu cultural practices. Polygamy was a common practice in the past but today, it is only practiced by few people, usually, if the man marries under traditional African law or Muslim law. Civil marriages (conducted by government authorities) and Christian marriages preclude the possibility of polygamy.

About 10 to 15 families traditionally made up a village, headed by a village headman (Omukasa). Oweliguru is a post-colonial title for a village leader coined from the English word “Crew.” Within a family, the man of the home was the ultimate authority, followed by his first-born son. In a polygamous family, the first wife held the most prestigious position among women.

The first-born son of the first wife was usually the main heir to his father, even if he happened to be younger than his half-brothers from his father’s other wives. Daughters had no permanent position in Luhya families as they would eventually become other men’s wives. They did not inherit property and were excluded from decision-making meetings within the family. Today, girls are allowed to inherit property, following Kenyan law.

Children are named after the clan’s ancestors, after their grandparents, after events, or the weather. The paternal grandparents take precedence, so that the first-born son will usually be named after his paternal grandfather (Kuka or ‘Guga’ in Maragoli) while the first-born daughter will be named after her paternal grandmother (‘Kukhu’ or ‘Guku’ in Maragoli.)

Subsequent children may be named after maternal grandparents, after significant events, such as weather, seasons, etc. The name Wafula, for example, is given to a boy born during the rainy season (ifula). Wanjala is given to one born during famine (injala).

Traditionally, they practiced arranged marriages. The parents of a boy would approach the parents of a girl to ask for her hand in marriage. If the girl agreed, negotiations for dowry would begin. Typically, this would be 12 cattle and similar numbers of sheep or goats, to be paid by the groom’s parents to the bride’s family. Once the dowry was delivered, the girl was fetched by the groom’s sisters to begin her new life as a wife.

Instances of eloping were and are still common. Young men would elope with willing girls, with negotiations for a dowry to be conducted later. In such cases, the young man would also pay a fine to the parents of the girl. In rare cases abductions were normal, but the young man had to pay a fine. As polygamy was allowed, a middle-age man would typically have two to three wives.

When a man got very old and handed over the running of his homestead to his sons, the sons would sometimes find a young woman for the old man to marry. Such girls were normally those who could not find men to marry them, usually because they had children out of wedlock. Wife inheritance was and is also practiced.

A widow would normally be inherited by her husband’s brother or cousin. In some cases, the eldest son would inherit his father’s widows (though not his mother). Modern-day Luhyas do not practice some of the traditional customs as most have adopted a Christian way of life. Many Luhyas live in towns and cities for most of their lives and only return to settle in the rural areas after retirement or the death of their parents there.

They had extensive customs surrounding death. There would be a great celebration at the home of the deceased, with mourning lasting up to forty days. If the deceased was a wealthy or influential man, a big tree would be uprooted and the deceased would be buried there. After the burial, another tree Mutoto, Mukhuyu or Mukumu would be planted. (This was a sacred tree and is found along most Luhya migration paths; it could only be planted by a righteous lady, mostly a virgin or a very old lady.)

Nowadays, mourning takes less time (about one week) and the celebrations are held at the time of burial. “Obukoko” and “Lisabo” are post-burial ceremonies held to complete mourning rites.

Animal sacrifices were traditionally practiced. There was great fear of the “Abalosi” or “Avaloji” (witches) and “Babini” (wizards). These were “night-runners” who prowled in the nude running from one house to another casting spells.

Religious Conversion

Most modern-day Luhyas are Christians; for some (if not all) the word for God is Nyasaye or Nyasae (Were Khakaba).

The word Nyasae when translated into English roughly corresponds with Nya (of) and Asae/ Asaye/ Sae/ Saye (Prayer). The Luhya traditionally worshiped an ancient ‘god’ of the same name (commonly known as Isis, or Were Khakaba. When Christianity was re-introduced to the Luhya in the early 1900s by Christian missionaries from Europe and America, the Luhya peoples took the name of their traditional god, Nyasae, and gave that name to the Living Abrahamic God.

The first Luhyas who were converted to Christianity took words, names, their perceptions of what Christian missionaries told them about the Christian God, and other aspects of their indigenous religious traditions, and applied them to their interpretations of Christ and God.

The Friends Church (Quakers) opened a mission at Kaimosi and the Church of God took over the mission in Bunyore. During the same period, the Catholic order Mill Hill Brothers came to the area of Mumias. The Church of God of Anderson, Indiana, US, arrived in 1905 and began work at Kima in Bunyore. Other Christian groups such as the Anglicans (CMS) came in 1906. In 1924 the Pentecostal Assemblies of Canada began their work in Nyan’gori. The Salvation Army came to Malakisi in 1936. The Baptists came to western Kenya in the early 1960s.

The first Bible translation in a Luyia language was produced by Nicholas Stamp in the Wanga language. Osundwa says he did this translation in Mumias, the former capital of the Wanga kingdom of Mumia.

A religious sect known as Dini ya Msambwa was founded by Elijah Masinde in 1948. They worship “Were,” the Bukusu god of Mt. Elgon, while at the same time using portions of the Bible to teach their converts. They also practice traditional arts referred to by some as witchcraft. This movement originally arose as part of an anti-colonial resistance.

Various sources estimate that 75%-90% profess Christianity.

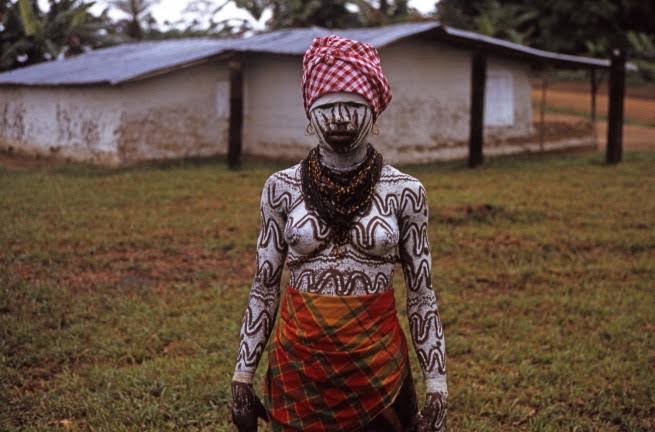

Initiation

With the smugglers of the Marama and Saamia, male circumcision was practised. A few sub-ethnic groups practiced clitoridectomy but, even in those, it was limited to a few instances and was not as widespread as it was among the Agikuyu. The Maragoli did not practice it at all. Outlawing of the practice by the government led to its end, even though it can occur among the Tachoni.

Traditionally, circumcision was part of a period of training for adult responsibilities for the youth. Among those in Kakamega, the initiation was carried out every four or five years, depending on the clan. This resulted in various age sets notably, Kolongolo, Kananachi, Kikwameti, Kinyikeu, Nyange, Maina, and Sawa in that order.

The Abanyala in Navakholo initiates boys every other year and notably on even years. The initiates are about 8 to 13 years old, and the ceremony was followed by a period of seclusion for the initiates. On their coming out of seclusion, there would be a feast in the village, followed by a period of counselling by a group of elders.

The newly initiated youths would then build bachelor-huts for each other, where they would stay until they were old enough to become warriors. This kind of initiation is no longer practiced among the Kakamega Luhya, except for the Tiriki.

Nowadays, the initiates are usually circumcised in hospital, and there is no seclusion period. On healing, a party is held for the initiate — who then usually goes back to school to continue with his studies.

Among the Bukusu, the Tachoni and (to a much lesser extent) the Nyala and the Kabras, the traditional methods of initiation persist. Circumcision is held every even year in August and December (the latter only among the Tachoni and the Kabras), and the initiates are typically 11 to 15 years old.

Also, See other Indigenous people.

African Great Lakes

Hadza people, Sandawe people, Twa people, Bangweulu Batwa, Great Lakes Twa, Kafwe Twa, Lukanga Twa, Nilo-Saharan, Kalenjin people, Maasai people, Samburu people, Bantu languages, Abagusii People, Kikuyu people, Luhya people, Bukusu, Afroasiatic, Iraqw people, Rendille people.

————————————————————————