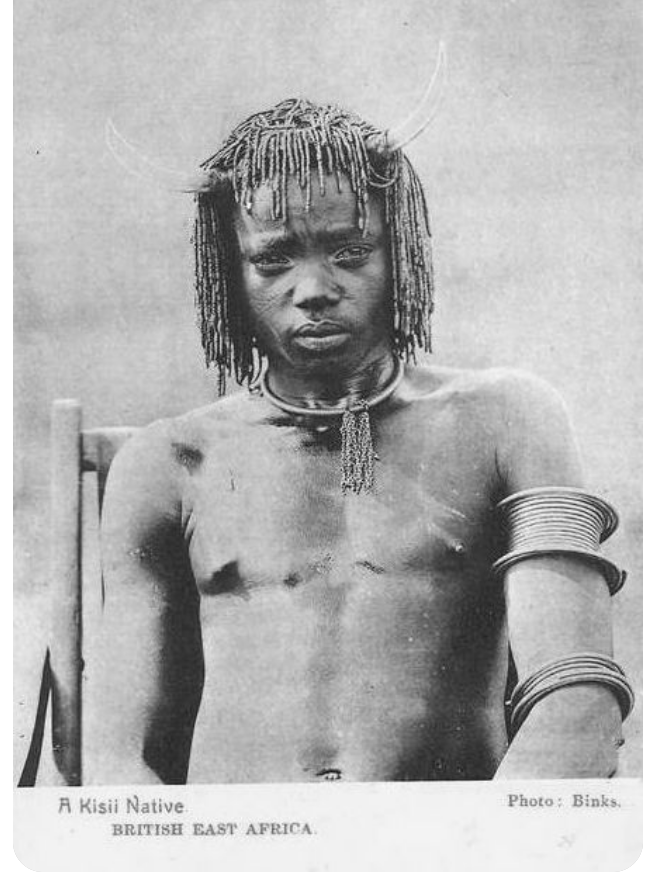

Kisii/Abagusii People

The Abagusii (also known as Kisii (Mkisii/Wakisii) in Swahili, or Gusii in Ekegusii) is an East African ethnic group with diverse origins that largely and inevitably originate from the Neolithic Agropastoralist and hunter/gatherer inhabitants of present-day Kenya particularly former Nyanza and Rift Valley provinces of Kenya. These Neolithic Agro Pastoralists were of the same stock as the ancestors of the modern Nilotes, Omotic and Cushites as well as the ancient East African hunter/gatherers similar to Ogiek and are the original progenitors of the majority of the modern Abagusii people. However, a minority of the Abagusii are believed to have been assimilated from the Luhya and Olusuba speaking Suba people (Kenya) that are believed to have migrated from the West of Lake Victoria that is present-day Buganda and Busoga in the 1800s hence originally from Central Africa/West Africa by the way of Bantu expansion. The majority of Abagusii are closely related to the Maasai, Kipsigis, Abakuria, and Ameru of Kenya. They also have a close linguistic relationship with Ngurimi, Rangi, Mbugwe, Simbiti, Zanaki and Ikoma people. However, a lot of evidence from studies of East African Bantu languages and anthropology suggests that the Abagusii and the mentioned related tribes emerged from the neolithic Agropastoralists and hunters/gatherers of East Africa believed to have come from the North of Mt. Elgon. The Abagusii traditionally/natively inhabit Kisii County (formerly Kisii District) and Nyamira County of former Nyanza Province of Kenya as well as parts of Kericho County and Bomet County of the former Rift Valley province of Kenya. The Abagusii are also found in other regions of geographical Western Kenya including former Nyanza Province such as Homa Bay County, and the rest of Luo-Nyanza as well as the rest of Kenya through recent migrations in post-colonial Kenya. There is also a significant diaspora population of Abagusii in countries such as the United States (especially in Minnesota state), United Kingdom, Canada, New Zealand, Australia, and South Africa among other countries within and outside Africa. The Abagusii speak Ekegusii language which is classified together with the Great Lakes Bantu languages. However, the inclusion of Abagusii in the Bantu language group is a subject of debate given that studies on East African Bantu languages have found the Ekegusii together with Kuria, Simbiti, Ngurimi, Rangi and Mbugwe languages to be far distinct from the typical Bantu in terms of structure and tense-aspect. Mogusii is culturally identified as its founder and patriarch. The Abagusii are, however, unrelated to the Kisi people of Malawi and the Kissi people of West Africa, other than the three very distinct communities having similar sounding tribal names. The traditional occupation of Abagusii in pre-colonial Kenya included hunting and gathering, pastoralism/herding and cereal (millet, sorghum), fruit (pumpkin) and root crop farming forms of Agriculture with pastoralism being the dominant occupation of Abagusii in pre-colonial Kenya. Today the Abagusii have adopted other forms of agriculture through interaction with the European colonists that introduced new crops and new cultivation methods to Gusiiland and Kenya as a whole with the same applying to the other African countries/communities. Some of these factors have ensured farming to be the most dominant economic activity among Abagusii as opposed to pre-colonial Kenya where they were predominantly pastoralists and hunters and gatherers.

Kisii town – known as Bosongo or Getembe by the locals – is located in Nyanza Province to the southwest of Kenya and is home to the Abagusii people. However, the term Kisii refers to the town and not to the people. The name Bosongo is believed to have originated from Abasongo (to mean the Whites or the place where white people settled(d)) who lived in the town during the colonial times. According to the 1979 census, Kisii District had a population of 588,000. The Abagusii increased to 2.2 million in the latest Kenya Census 2009.

Etymology of the word Kisii

The term Kisii is a Swahili name and originates from the colonial British administration who used it in colonial Kenya (the 1900s) to refer to the Abagusii people. The term was popularly used during the colonial period by the British administration in reference to Abagusii as it was much easier to pronounce. The term Kisii however has no meaning in Ekegusii language as it is a Swahili term. In the Swahili language, the singular form of the word is Mkisii and the plural form is Wakisii which only makes sense in the Swahili language and related coastal and Central Bantu languages of Kenya. The Swahili name for the Ekegusii language is Kikisii. The term has existed since the 1900s when it was coined by the British and is now popularly used in Kenya to refer to Abagusii people although that is not what they are called. Among Abagusii the name Kisii is used to only mean Kisii town and not to the people. The other names used by the British in reference to Abagusii during the colonial period were Kosova/Kossowa which is derivative of the Ekegusii expression “Inka Sobo ” which means their home. The name Kosova is not currently used among the Abagusii people although the Kipsigis use the derivatives of the term Kosova such as Kosobek/Kosobo in reference to the Abagusii people. The original and correct name by the people for themselves is Omogusii in singular and Abagusii in a plural and the language spoken by the people in Ekegusii. The term Gusii comes from Mogusii who was the founder of the community. However, the speculation that the term Gusii comes from Gwassi is incorrect and the Abagusii never lived near Gwassi hills of the modern Homa Bay County and Gwassi is a Luo-Abasuba name for one of their sub-groups. The Abagusii are indigenous to Nyamira and Kisii counties and sections of Kericho and Bomet counties of the former Rift Valley province of Kenya. The speculation that the Abagusii lived in or passed through modern-day Kisumu County in the course of their migration and settlement in Nyanza are mere opinions that are absurd and too far-fetched given that the so-called migrations did not occur. There is a lack of evidence that the Abagusii migrated from Luo-Nyanza counties of Siaya, Kisumu, Homa Bay and Migori. The four Luo-Nyanza counties have always been inhabited by the Luos who are indigenous to the shores of Lake Victoria which clearly means that the speculation that the Abagusii migrated from there clearly makes no sense. The Abagusii have only settled in the major towns of these four counties in the post-colonial period. Some of the other non-Luo tribes such as Luhya were settled in some of the Luo-nyanza counties like Homa Bay, Migori, Kisumu and Siaya counties by the British government to clear bushes and chase tsetse flies and opted to stay there. The Abagusii and Kuria related Simbiti/Egesuba speaking Suba-girango and Suba-simbete of Migori County and sections of Homa Bay County as well as Northern Tanzania migrated from Gusii and Kuria lands to Luo-Nyanza and other regions where found. The Olusuba speaking Suba people (Kenya) of Rusinga Island, Mfangano Island and sections of Homa Bay County migrated from Buganda, Busoga and Luhyaland in the 1800s and indeed the Olusuba language is very similar to Luganda, Lusoga and Luhya languages such as Olusamia and other Luhya languages. The only tribes that are truly from the four counties of Luo-Nyanza are the Luo that is indigenous and forms over 95% of the Luo-Nyanza population as well as the minority Kuria native to the former Kuria District of Migori County. The Olusuba speaking Suba people (Kenya) only settled in Rusinga Island, Mfangano Island and other sections of Homa Bay County in the 1800s. The earlier Suba groups like Suba-Girango, and Suba-Simbete migrated from Gusiiland and Kurialand to Luo-Nyanza. The terms “Gwassi” and “Gusii” don’t really even sound or look-alike as an ordinary ignorant person may assume. The two terms have distinct pronunciations and Etymology. The term “Gwassi” originates from the Olusuba language spoken by Luo-Abasuba and is used to refer to one of their sub-groups and Gwassi hills. The term “Gusii” on the other hand, originates from the Ekegusii and specifically from the name “Mogusii” who was the founder of the community. The term “Gusii” is not used as a reference to any geographical features such as hills in Gusiiland which is commonly referred to as Gusii highlands due to the presence of several hills in the region. The terms “Kisii” and “Gusii” are also not synonyms as most people tend to assume and have distinct etymology and pronunciation just like the terms “Gwassi” and “Gusii”. For instance, the term “Gusii” is phonetically pronounced as “Goosie” and the term Kisii is pronounced as “Keesie”. The Ekegusii language also does not have the “SS” but just “S” in its alphabet.

History

The Abagusii are indigenous to and traditionally inhabit Nyamira, and Kisii counties of former Nyanza and sections of Kericho and Bomet counties of the former Rift Valley province of Kenya. The Abagusii are also found in Luo-Nyanza counties such as Homa Bay, Migori, Kisumu and Siaya counties through recent migrations to major towns in these counties in post-colonial Kenya. The Abagusii are also found in other regions of Kenya in the same way. However, there is large linguistic and anthropological evidence that the Abagusii together with Kuria, Ngurimi, Rangi, Mbugwe, Simbiti, Zanaki and Ikoma people originate from the neolithic Agro Pastoralists of East Africa. The traditional occupations of Abagusii prior to the colonization of Kenya included Pastoralism and hunting/gathering and some minor forms of farming such as millet, sorghum and pumpkin farming. The Abagusii and other groups in Kenya and Africa as a whole have however, adopted other forms of Agriculture through interaction with the European colonists that introduced new crops and farming methods to Gusiiland and the rest of Kenya and Africa.

Origins

Based on linguistic and anthropological evidence, the Abagusii originated from the neolithic Agropastoralist inhabitants of present-day Kenya particularly former Nyanza and Rift Valley provinces. Indeed, the studies on East African Bantu languages indicate that the Ekegusii together with Kuria, Ngurimi, Rangi, Mbugwe and Simbiti languages significantly differ from the typical Bantu languages in structure and tense. The mentioned languages have been found to be more similar to the Nilotic and Cushitic languages and only have some lexical similarities to the Bantu languages. This is clear evidence that the Abagusii together with Kuria, Rangi, Ngurimi, Mbugwe, and Simbiti originated from earlier neolithic Agro Pastoralists of East Africa from whom they inherited their respective languages. Indeed, Johnston (1886), relates that the Loikop were “divided into many classes, tribes and even independent nations’ ‘. He grouped separately the divisions of the Masai and those of the Kwavi, noting that the latter was “settled agriculturalists’ ‘. Among the Kwavi divisions that he recognized were Kosova, along with the En-jemsi and the district of Lake Baringo, Laikipia, Lumbwa (near Kavirondo), Aruša, Méru (near Kilimanjaro), Ruvu river, Nguru (south) These agropastoralists were later joined by a later group of Bantu speakers from the West of Lake Victoria from present-day Buganda and Busoga that were assimilated from the Olusuba speaking Suba people (Kenya).

Contrary to the popular belief that the neolithic Agropastoralist inhabitants of East Africa were assimilated by the Bantu speakers and adopted their languages, the available evidence indicates that it is the Bantu speakers who adopted the languages of the agropastoralists that preceded them in East Africa. Indeed, some of the Bantu speaking people such as the Abagusii and the mentioned tribes with non-typical Bantu languages emerged from the supposedly extinct agropastoralists. This school of thought is particularly true of the Bantu languages and cultures of the wider Eastern Africa region that has historically been inhabited by ancient Agro Pastoralists from the North. However, the oral literature of Abagusii inherited from their agro pastoralist ancestors supplemented with written scholarly works, indicate that they migrated to present-day Kenya from areas further North of Mt. Elgon region of Kenya. This pre-Elgon homeland of Abagusii is referenced as Misiri and is a general area to the North of Mt. Elgon does not state that Misiri is Egypt. This Misiri homeland is realistically the Nile Valley region adjacent to modern-day Ethiopia due to migration through the Rift Valley province of Kenya and settlement at the Mt. Elgon region of Kenya is largely part of the Rift Valley. They migrated along a great mythical river called Riteru and passed through a desert land, Eroro. The Misiri homeland of Abagusii is unconnected to the so-called popular Hamitic hypothesis by C.G. Seligman on the migration of Hamites from North Africa that introduced advanced civilizations to Sub-Saharan Africa. The oral traditions similar to those of Abagusii are also found in the Abamaragoli, Ameru and Kuria. Similar oral traditions are also found in some Kalenjin tribes, some (especially Kipsigis) of who are related to Abagusii and/or migrated together with Abagusii despite being linguistically classified as Nilotic. As the Abagusii migrated from their semi-mythical homeland(Misiri), they first settled at the Mt. Elgon region of Kenya for several years before migrating to their current homeland. From Mt. Elgon, the Abagusii migrated to Nyanza Province near Lake Victoria and are believed to have migrated together with the Ameru and the Abamaragoli whose oral traditions are somewhat similar to those of Abagusii. The Abamaragoli settled in Western Kenya and the Ameru, Embu, Mbeere and Kikuyu later migrated to the former upper Eastern and Central provinces of Kenya where they later formed relationships with neighbouring communities such as Borana people and communities in Central and lower Eastern provinces of Kenya. However, the speculation by some scholars that the Abagusii migrated from Uganda is inaccurate and they have never been to Uganda. The Abagusii only settled on the Eastern slopes that are the Kenyan side of Mt. Elgon which is in the Rift Valley province. The Abagusii are also unrelated to the Bantu speaking communities in Eastern Uganda such as Abasoga, Masaba people, and other tribes in the same region both linguistically and culturally. The Bantu speaking communities in Eastern Uganda as well as Buganda and Western Uganda are largely part of and/or related to the Luhya people of Kenya in language, physique and culture. The only tribes that factually migrated to Kenya from Uganda are the Luo, Luo-Abasuba and some Luhya tribes. The Luo and Luhya are from Eastern Uganda while the Olusuba speaking Luo-Abasuba are mostly from Buganda and some from Busoga. Some of the Olusuba speaking Suba people (Kenya) were assimilated by the Abagusii as well as Kuria and most of them were assimilated by the Luos. In Kenya, the Abagusii are most closely related with the Kuria and the Ameru of the former Upper Eastern Province in culture and language. Though close to Abagusii, their relationship is only tied to having similar oral traditions. Other than that, they are distinct in terms of culture and language and the Lulogooli is very distinct from the Ekegusii language spare some lexical items shared through interaction and intermarriage. The Abagusii and Abamaragoli don’t really understand each other and their cultures are also distinct from each other. Therefore, the speculation by some scholars that the Abagusii and Abamaragoli were originally one people is too far-fetched and absurd and it can only be a general opinion. The only languages that are almost mutually intelligible with the Ekegusii are the Egekuria, Kimiiru, Ikizanaki, Ngurimi and Simbiti/Egesuba (not to be confused with the Olusuba of Luo-Abasuba ) of the Suna-Girango and Suba-Simbete. In fact, the Abagusii even have more in common in several aspects with the Luo and Kipsigis than they have with the Abamaragoli that are presumed to have been originally one people with Abagusii. The same can be said about the relationship between the Abagusii and the Bantu speaking tribes in East Africa and Africa as a whole.

The immediate neighbours of Abagusii include the Kuria, Luo, Kipsigis, Nandi and Maasai. A number of clans of these neighbouring communities, especially the Kipsigis have Abagusii origins. During the pre-colonial period the Abagusii and the neighbouring communities engaged in Barter trade, some of which led to the formation of modern-day Kisumu city of Nyanza Province. The Abagusii are naturally very industrious and resilient despite engaging in some minimal cattle rustling activities with their neighbours. The Bantu speaking community with a great many similarities with the Abagusii is the Meru people (Abameru in ekegusii) from the windward slopes of Mount Kenya, although the Kuria people (Abatende in ekegusii) share a great deal in common with the Abagusii in language and culture as well, and history of intermarriage has led to the prohibition of marriage alliances for specific clans of the Abagusii with some Kuria clans. Additionally, intermarriages between members of the same clans are prohibited.

Origins and the Nile Valley

Present-day Kenya and Eastern Africa region at large has been inhabited since the Neolithic period. The first inhabitants of Kenya were hunters/gatherers similar to Khoisan and Ogiek. These hunters were closely followed by ancient Agro-pastoralists from North Africa and Horn of Africa that are believed to have settled in present-day Kenya during the Savanna Pastoral Neolithic period (ca.3200-1300 BC) that are believed to have completely replaced and/or assimilated the hunter/gatherer population that presided them. These ancient agro-pastoralists were followed by the Nilotic speaking pastoralists from present-day South Sudan that are believed to have settled in Kenya around 500 BC. The last group of people to settle in Kenya and Eastern Africa at large are the Bantu speakers believed to have migrated from Central Africa or West Africa and settled in Kenya beginning the first millennium AD (1 AD). This leads to the conclusion that the Cushites, Kalenjin, Luo, Maasai and Ateker are among the earliest settlers of present-day Kenya and the general Lake Victoria Basin, which comprises modern-day Rwanda, Northwest Tanzania, Uganda and geographical western Kenya. Among the Bantu speaking communities, the Abagusii together with Luhya is believed to be the earliest to settle in Kenya. The actual migrations and settlement of Abagusii in Kenya during the pre-colonial period can be tracked to the Mt. Elgon region of the Northern Rift Valley of Kenya. The Mt. Elgon region of Kenya is in fact the original point of dispersal of Abagusii to other regions of Kenya where they settled during the pre-colonial period as well as their current homeland in Nyanza province of Kenya. The oral literature of Abagusii indicates that prior to settlement at the Mt. Elgon region, they migrated from areas further North of Mt. Elgon. This pre-Elgon homeland is referenced as Misiri according to the oral literature of Abagusii and does not state that Misiri is Egypt. In fact, Egypt as a country did not exist in pre-colonial Africa and was created in the 1950s by European conquerors just like other present African countries and the naming of the modern country of Egypt was done by Europeans. Therefore, the Abagusii like other Africans did not know Egypt as the name did not exist in pre-colonial Africa. In that sense, the Misiri homeland of Abagusii is not referring to Egypt which is a country that never existed in pre-colonial Africa. Although Misiri is sometimes automatically assumed to mean the modern Egypt country and the lost tribes of Israel, the Misiri homeland of Abagusii does not refer to Egypt and the lost tribes of Israel. The Misiri homeland of Abagusii does not refer to a specific area to the North of Mt. Elgon, but rather a general area to the North of Mt. Elgon. This Misiri homeland to the North of Mt. Elgon is realistically the Nile Valley region adjacent to modern Ethiopia which lies to the North of Mt. Elgon. During migration and settlement in present-day Kenya, the Abagusii passed through the Rift Valley and settled at the Mt. Elgon region which is part of the Rift Valley. This justifies the location of Misiri homeland of Abagusii at the Nile Valley region adjacent to Ethiopia which all lie to the North of Mt. Elgon. The oral literature, migration and settlement patterns of Abagusii in Kenya as well as linguistic and anthropological evidence suggest that the Abagusii share origins with and/or are an offshoot of the Nilotic speaking peoples hence migrated together with the Nilotes rather than the migrating together with the Bantu speakers. Indeed, recent studies of East African Bantu languages indicate that Ekegusii together with Kuria, Simbiti, Rangi, Mbugwe, and Ngurimi languages are far distinct from typical Bantu languages in terms of structure and tense aspect and more similar to the Cushitic and Nilotic languages. Although the Nile Valley region is generally assumed to be a homeland of the Nilotic speaking and some Cushitic speaking communities, it is also a homeland to Abagusii together with Kuria, Simbiti, Ngurimi, Rangi, Mbugwe, Zanaki, Ikoma and Ameru tribes which are believed to have been part of the Abagusii a few centuries ago. This is supported by strong cultural similarities between Abagusii as well as the mentioned related tribes and some Cushitic speaking and Nilotic speaking communities in Kenya, South Sudan, Sudan and Ethiopia. The majority of Abagusii and the mentioned related tribes inevitably emerged from the Sirikwa/Loikop peoples and cultures which were connected to the Cushitic and Nilotic speaking communities. Some of the Abagusii and the mentioned related tribes migrated from Central Africa/West Africa by the way of Bantu expansion and were later additions to the Sirikwa/Loikop from whom they most likely inherited their respective languages, cultures and myths of origin from the North. This is a clear explanation as to why the languages of the mentioned tribes are non-typical Bantu languages in terms of structure. The general conclusion is that some of the so-called Bantu speakers originated from the neolithic pastoralist and agro-pastoralist inhabitants of Eastern Africa rather than expanding from Central Africa/West Africa.

Origins and the Niger-Congo Hypothesis (The Bantu Expansion Theory)

The concept of migration and movement of indigenous African peoples within Africa was first pioneered by Wilhelm Bleek in the 1850s who coined the term “Bantu” to refer to the non-Khoisan South Africans that used the term “Abantu” and Similar words in reference to “People or Human Beings. According to Wilhelm Bleek, these tribes appeared to have a common origin on the basis of using words very similar to “Abantu ” in reference to “people or Human beings”. These concepts were advanced further by later European scholars such as Joseph Greenberg who later developed the Niger-Congo hypothesis and created the Niger-Congo linguistic classification as well as other African linguistic groups such as Nilo-Saharan, Cushitic, Hamitic, Afro-Asiatic, Nilotic, Sudanic, West Sudanic (West Africans), and Khoisan The Bantu expansion forms a large percentage of the Niger-Congo hypothesis which postulates that the Bantu speakers expanded from the border of Nigeria and Cameroon to other regions of Africa where they are found. This theory was subsequently advanced by Malcolm Guthrie who later subdivided the Bantu sub-family of the Niger-Congo languages into regions and came up with the concept of the migration of the Bantu speakers from Katanga of the Southeast Democratic Republic of the Congo and Central Africa in general. The Bantu linguistic group was further developed with the creation of Great Lakes Bantu languages that were added to Guthrie’s classification as Zone J. In the context of Abagusii, the Ekegusii was included in the Great Lakes Bantu languages family. The Niger-Congo hypothesis and the Hamitic hypothesis as well as the creation of current African linguistic groups are the very crucial factors that laid a foundation to the current written history of African peoples that is taught in African schools today. For instance, the written African history for all indigenous African peoples dates to the 1850s and 1900s when various theories on the origins and migrations of African peoples within Africa were developed. In that sense, the Abagusii, like other indigenous African peoples, have a written history dating to the creation of the Niger-Congo hypothesis and Niger-Congo as well as the Bantu sub-family. Prior to the creation of the Niger-Congo, the Abagusii history was passed down from generation to generation through oral means. Today this history acquired from oral sources has been combined with the history learnt from school creating the current written history of the Abagusii. For instance, the original oral history of Abagusii indicates migration from the North of the Mt. Elgon region of Kenya from a semi-mythical place referenced as Misiri. However, the knowledge acquired from schools on the history and migrations of African linguistic groups has transformed the thought process of all Africans including the Abagusii. For instance, the Abagusii have incorporated the concept of migration from Katanga of the Democratic Republic of the Congo and the border of Nigeria and Cameroon as well as the general Central African region to their original oral history. The names of countries such as Nigeria, Cameroon, Democratic Republic of Congo/Zaire, and Niger were created by the European conquerors in the mid-1950s and as such these mentioned names of countries did not exist in Africa with exception of Congo/Zaire which originates from the Kongo people. Therefore, most Africans lack the names of the mentioned countries in their lexicon and have acquired the knowledge of these countries through modern education on African countries and linguistic groups. In fact, the Niger-Congo and Hamitic hypotheses have influenced and transformed the thought process of all indigenous African peoples in several ways. For instance, the Niger-Congo hypothesis assumes a mass migration of the Bantu speaking peoples from the border of Nigeria and Cameroon and the introduction of iron tools and agriculture to Eastern, Central and Southern Africa regions of Africa. This has contributed to the false sense of supremacy and beliefs among the Bantu speaking tribes that they are more advanced than the other African linguistic groups and are the owners of farming and iron tools technology. On the other hand, the Hamitic hypothesis assumes that the Cushitic speaking communities and as well as Nilotic peoples are the pioneers of Animal herding/pastoralism and introduced advanced civilizations to Sub-Saharan Africa. This has also given the mentioned linguistic groups a false sense of superiority and belief that they are owners of cattle as compared to their Bantu speaking counterparts. The practice of Pastoralism/herding, farming, and iron tools technology are quite evenly distributed in all African linguistic groups and were acquired independently rather than being spread from one group or region to another. The general conclusion is that Bantu speaking peoples neither introduced the iron tools nor agriculture to Eastern, Central and Southern Africa and the so-called mass expansion of the several thousands of Bantu tribes from the border of Nigeria and Cameroon is too far-fetched and bizarre and did not occur. The same can be said about the association of pastoralism/herding to the Cushitic and Nilotic communities as well as the presumed mass migrations of these African linguistic groups.

Settlement in Gusiiland

Present-day Gusiiland has been inhabited since the Neolithic period just like the rest of Kenya and Eastern Africa at large and as such the settlers of present-day Gusiiland, which comprises Nyamira and Kisii counties of former Nyanza, came from different directions and are diverse in origin. The first settlers of Gusiiland were hunters/gatherers similar to Khoisan and Ogiek which were followed by the Nyanza/Rift Cushites who replaced and/or completely assimilated the ancient East African hunters/gatherers and settled in this area during the Savanna Pastoral Neolithic period (ca.3200-1300 BC). The next group of settlers were the Nilotic pastoralists from present-day South Sudan that settled in the area ca.500 BC. The last group to settle in this area are the Bantu speakers which settled in the area beginning 1 AD hence later additions to the pre-existing agro-pastoralist population. Therefore, the original and first settlers of Gusiiland came from the North of Mt. Elgon of the former Rift Valley province of Kenya from a semi-mythical area called Misiri. Based on linguistic and archaeological/anthropological evidence, these first settlers of present Gusiiland from the North (Misiri) were ancient agro-pastoralists and pastoralists of the same stock as the ancestors of the modern Cushites, Omotics and Nilotes although Bantu speaking. These ancient agro-pastoralists that is the Nyanza/Rift Cushites are the progenitors/founders of the major Gusii clans namely Abagetutu, Abanyaribari, Abagirango, Abanchari, Abamachoge, and Ababasi. The names of these six major Gusii clans and the eponym Gusii/Omogusii/Abagusii originate from these ancient agro-pastoralists that is the Nyanza/Rift Cushites. The Abagusii cultures, oral literature, Ekegusii language and totems also originate from these ancient agro-pastolarists that is the Nyanza/Rift Cushites. These ancient agro-pastoralists were the original Abagusii and were later joined by a later group of settlers from the West of Lake Victoria that is from present-day Buganda and Busoga who were later additions to some of these six Gusii clans by assimilation and language shift. The later group of settlers from the West of Lake Victoria were assimilated from the Olusuba speaking Suba that migrated to Kenya from Buganda and Busoga in the 1800s. Some of the settlers of present-day Gusiiland are believed to have come from the South, possibly present-day Tanzania, but there is insufficient evidence to support that. Moreover, the British introduced new immigrants to Kisii County and other parts of Kenya in the 1930s to work for them as soldiers, porters and farmers. This new immigrant settled in Kisii County included Baganda, Maragoli, Nubi and the Olusuba speaking Suba people (Kenya) from Rusinga Island, Mfangano Island and sections of Homa Bay County. The Nubians were settled by the British in present-day Kisii town and worked as soldiers for the British government, while the Bantu speaking Maragoli, Baganda and Suba people (Kenya) were settled in Kisii town as porters and labourers on White farms and tea plantations. Some of the new immigrants introduced to Kisii town by the British have been assimilated into the Gusii society for the case of Maragoli, Suba people (Kenya) and Baganda. Unlike the Bantu speaking immigrants, the Nubi never assimilated into the Gusii society and have maintained their original settlement in Kisii town.The ancient agro-pastoralists that is the Nyanza/Rift Cushites progenitor to the modern Abagusii people are the ones who introduced agriculture and iron tools to western Kenya and the rest of Kenya as well Great Lakes region of East Africa. Therefore, the agricultural practises of Abagusii as well as iron tools originate from these ancient agro-pastoralists. The Nyanza/Rift Cushites are also responsible for the pre-historic sites present in Kenya such as the Thimlich Ohinga and other sites in Kenya and Eastern Africa at large. The Nyanza/Rift Cushites are connected to the Sirikwa/Loikop cultures/peoples. Indeed, research on the people of present-day Kenya and neighbouring countries indicate that Kenya was originally inhabited by ancient agro-pastoralists of the same stock as the ancestors of modern Nilotes and Cushites. These ancient agro-pastoralists are believed to have given the rise to some of the Bantu speaking peoples such as the Abagusii, Kuria, Ngurimi, Simbiti, Rangi and Mbugwe. This same school of thought can be applied to the Tutsi people of Rwanda, Burundi, Tanzania, Uganda and East DRC as well as the Iraqw including other Southern Cushites of Northern Tanzania and the Rift Valley Nilotes such as the Kalenjin peoples as well as the Luo. In fact, some studies on East African Bantu languages show that Ekegusii, Kuria, Ngurimi, Simbiti/Egesuba, Rangi and Mbugwe languages are structurally different from typical Bantu languages and more similar to the Cushitic and Nilotic languages. The general conclusion is that the so-called Bantu speakers never expanded from anywhere, but rather emerged from the indigenous populations in Central, Southern, and Eastern Africa where they are found. The main conclusion that can be made here is that the Abagusii are a fusion between the neolithic agro-pastoralists that is the Nyanza/Rift Cushites aka Sirikwa from the North (Misiri) and Bantu from Central Africa. Another major conclusion that can be made here is that a majority of the so-called Bantu languages and cultures have been inherited from the neolithic agro-pastoralists from the North which were found in the entire region of Eastern Africa through intermarriage and assimilation. This notion is especially true of the Bantu languages and cultures of wider Eastern Africa, especially the non-typical Bantu languages such as Ekegusii, Kuria, Ngurimi, Simbiti/Egesuba, Rangi and Mbugwe. The Bantu tribes have been recipients rather than donors. In other words, they have been influenced, colonized and assimilated rather than influencing or assimilating or colonizing other peoples. That is contrary to the popular Niger-Congo Hypothesis which portrays them as being the most influential Africans.

Abagusii people in Pre-colonial Kenya

According to the oral literature of Abagusii supplemented with written scholarly works, the original progenitors of Abagusii migrated to their current homeland in Nyanza from areas further North of the Mt. Elgon region of Kenya and are the source of the Abagusii cultures, and language. This pre-Mt. The Elgon homeland of Abagusii is referenced as Misiri according to their oral literature. The Abagusii group from the North of Mt. Elgon were the original and first group of the Abagusii ancestral/progenitor to all the major Gusii clans namely, Abagetutu, Abanyaribari, Abamachoge, Abagirango, Ababasi and Abanchari. These Northern group of Abagusii from Misiri were connected and/or related to the Sirikwa/Loikop peoples/cultures and were later joined by the Abagusii group that is believed to have come from the west of Lake Victoria through the Olusuba speaking Suba people (Kenya) who were escaping the expansion of the Buganda kingdom in the 1800s. This group of Abagusii were assimilated by the original Northern group of Abagusii (Sirikwa/Loikop) from the Olusuba speaking Suba people indirectly through the Luos and the Abagusii and Kuria splinter groups such as the Simbiti/Ekisuba/Egesuba speaking Suba-Girango and Simbete that settled among the Luo. Another group of the Abagusii is believed to have come from the south although there is insufficient evidence of migration from the South. The Abagusii group from the south and west of Lake Victoria were later additions to the ancestral/progenitor and original Northern Abagusii (Sirikwa/Loikop) that were agro-pastoralists and hunters possibly of the same stock as the Cushitic and Nilotic speaking peoples although linguistically Bantu speaking from the semi-mythical Misiri. The Sirikwa/Loikop were also responsible for the introduction of Iron tools and agriculture to geographical western Kenya and the great lakes region as a whole. This leads to the conclusion that the Bantu speaking peoples learned the art of iron technology and agriculture from the Sirikwa/Loikop rather than introducing agriculture and iron tools to Eastern Africa. It can also be concluded that the Bantu speaking peoples never came from the north but rather interacted with people from the North from whom they inherited most of their myths of origins, cultures and most of the so-called Bantu languages.These diverse origins of Abagusii as well as different migration routes are illustrated by the very diverse appearance/physique among Abagusii ranging from negroid-like to caucasoid like appearance. The general conclusion that can be made here is that the Abagusii are a fusion between Sirikwa/Loikop peoples from the North (Misiri) and Bantu from Central Africa that were later additions to the Sirikwa/Loikop that preceded them in Eastern Africa. The other conclusion that can be made is that most of the so-called Bantu languages have been inherited through interaction and assimilation with other people. This notion is particularly true about the Bantu languages and cultures of the wider Eastern Africa that has historically been inhabited by ancient agro-pastoralists from the North similar to Sirikwa/Loikop. This Misiri homeland is realistically the Nile Valley region adjacent to modern Ethiopia due to migration through the Rift Valley Province of Kenya. After migrating from Misiri, the Abagusii passed through the present day Rift Valley province of Kenya and first settled at the Mt. Elgon region of present-day Kenya where they stayed for several years before migrating to present-day Nyanza province. The Mt.Elgon region of Kenya is the original point of dispersal of Abagusii to other regions of Kenya where they settled during the pre-colonial period as well as their current homeland in Nyanza Province of Kenya. In fact, the actual migrations of Abagusii can be tracked to Mt. Elgon region of Kenya as well as the Rift Valley province of Kenya. At the Mt. Elgon region of Kenya, the Abagusii came into contact with Luhya tribes most of whom had migrated from Uganda as well as Ogiek people. The Abagusii could have migrated together with and/or interacted with some Kalenjin groups, Maasai and Luo as well as the Bantu speaking tribes such as Abamaragoli, Abakuria, Ameru, Embu, Kikuyu, Zanaki, Rangi, Mbugwe, Ngurimi, and Ikoma who are very similar to Abagusii in some aspects. During their stay at Mt. Elgon region, the Abagusii were mainly herders that kept cattle, goats, sheep, with minimal crop cultivation of finger millet, sorghum and root crops among other local crops available then. The Abagusii also practised some hunting and gathering (a practice that was borrowed from the Ogiek people of Mt. Elgon) to supplement the food they obtained from their animals and crops. The land at the Mt. Elgon area became unfavourable for their animals and crops thus forcing the Abagusii to migrate in search of good land mainly for pasture and cultivation of crops. At this time, the Abagusii migrated to the South Rift and eventually to the Nyanza region whereas, the Ameru, Kikuyu, Embu, and Mbeere migrated to the upper Eastern province and Central province. The other groups believed to have migrated together with Abagusii such as Abamaragoli migrated to the Western province of Kenya.

The Abagusii are believed to have settled in parts of present-day Bomet and Kericho counties before settling in present-day Nyamira and Kisii counties. At Kericho and Bomet, the Abagusii are believed to have built fortified walls with thick thorn fences and dug deep trenches around their homesteads as a defence against cattle theft and raids by the Maasai and Nandi who have always been their immediate neighbours. The Abagusii and Siria-Maasai indeed lived side by side for several years in Kericho and Bomet before Abagusii migrated to Gusii highlands. A number of clans from the Nandi and Tugen as well as other Kalenjin tribes later migrated to Kericho and this led to turmoil between them and Abagusii as well as the Siria-Maasai. They first drove the Maasai out of Kericho before doing the same to the Abagusii who stayed at what came to be known as Kabianga. Their attempts to drive the Abagusii out of Kericho were unsuccessful as the Abagusii were more armed and had stronger warriors than the Maasai who raided them at night for that reason. Some of the Abagusii families/clans remained in Kericho and merged with the Nandi, Tugen and other Nilotic Kalenjin clans as well as Ogiek forming the modern-day Kipsigis tribe. However, a majority of the Abagusii were forced to migrate out of Kericho and Bomet due to very dense forests which made the area cold and unfavourable for livestock and hunting/gathering and to a lesser extent crop cultivation which was a minor activity until the 19th century with the introduction of new crops and farming methods by the European colonists. The Abagusii named the region where they stayed in Kericho “Kabianga” which means “to refuse” to imply that crops and pasture for their livestock refused to grow. In fact, most Abagusii cattle died and crops failed which caused famine and death of members of the community and this forced them to migrate to Kisii and Nyamira counties. This led to the split of the Abagusii and Abakuria into two tribes with the Abakuria migrating following the shores of river Gucha/Kuja to modern Migori County and eventually to Northern Tanzania where most of them reside today. This is the clear explanation of why almost all Kuria clans are of Gusii origins except those few clans that the Kuria have assimilated from other communities such as Olusuba speaking Suba people (Kenya) and other communities in Tanzania. The Abakuria group that settled in Northern Tanzania particularly the Mara and Lake Victoria regions of Tanzania formed other tribes that populated much of the Mara and lake Victoria region as well as other sections of Northern Tanzania. A good example of such other closely related tribes includes; Zanaki, Ngurimi, Rangi, Mbugwe, Simbiti and Ikoma of Northern Tanzania. The Abagusii dispersed from the sections of Kericho County and Bomet County where they traditionally inhabit Nyamira County and eventually to Kisii County which were also originally forested just like Kericho and Bomet counties. The general conclusion is that the Kuria and the mentioned related tribes of Northern Tanzania were part of the Abagusii, but split into different tribes due to famine, cold climate and unfavourable land conditions in sections of Kericho and Bomet counties from which they dispersed to current lands. This is a clear explanation of why the languages of Kuria and the mentioned related tribes of Northern Tanzania are very similar to the Ekegusii. After permanently settling in Nyamira and Kisii counties, some of the Abagusii are believed to have recently settled in the Luo-Nyanza counties of Siaya, Kisumu, Migori and Homa Bay among the Luos through assimilation. The Abagusii and Kuria splinter groups that settled among the Luo are the ones that led to the formation of the Suba-Girango and Suba-Simbete. While there is a lack of evidence that the Abagusii migrated from modern-day Kisumu County to Gusiiland, it is generally presumed by some scholars that they settled close to the shores of Lake Victoria at modern-day Kisumu County. These assumptions of the Abagusii migration from Luo-Nyanza counties are rather absurd and based on guesswork given that the Abagusii have settled in the major towns of the Luo-Nyanza counties during the post-colonial period. Moreover, the majority of the Abagusii found among the Luo have assimilated into the Luo cultures rather than migrating from there. The Abagusii later had indirect contact with a later small Bantu speaking group from Uganda particularly Buganda and Busoga that settled in Rusinga Island, Mfangano Island and sections of Homa Bay County during the 1800s. The contact between Abagusii and these smaller Bantu was facilitated by the Luo who form a buffer zone between the two communities as well as the Suba-simbete, and Suba-girango who are splinter groups from Abagusii and Kuria that have settled among the Luo people in phases and assimilated into Luo cultures since many years prior to colonization of Kenya. A good example of such Bantu group from Uganda is the Aweluzinga, Awivangano, Awakune and Awigassi (Gwassi) tribes (including some of their respective sub-tribes) of the Luo-Abasuba (not to be confused with Suba-Simbete and Suba/Suna-girango who are splinter groups from Abagusii) whose Olusuba language is very different from Ekegusii, Egikuria, and Dholuo language, as well as other languages, are spoken in Nyanza. The Olusuba language is very similar to the Luganda, Lusoga and some Luhya languages such as Olusaamia and Olunyala. A majority of the Olusuba speaking Suba at the shores of Lake Victoria and the islands of Lake Victoria were later assimilated by the Luo through language shift. Some of them were also later assimilated by the Kuria and to a lesser extent the Abagusii. The Olusuba speaking Suba people (Kenya) assimilated by the Abagusii were mainly assimilated by some of the South Mugirango clans and some of the Bobasi clans around Sameta town and are a minority of the Ababasi and southern Abagirango clans/tribes and the Abagusii community at large. The general conclusion is that the Abagusii are indigenous to and traditionally inhabit Kisii and Nyamira counties as well as sections of Kericho and Bomet counties. Therefore, the assumptions by some scholars that the Abagusii migrated from Kisumu County at the shores of Lake Victoria are too far-fetched and absurd and are just mere opinions and guesswork.

The Abagusii have gradually cleared the forests in Gusii highlands with time after permanent settlement in the region primarily for settlement and herding as well as crop cultivation as more new crops such as tea, coffee, maize and several other exotic/foreign crops became available in the 19th century through the European colonists. There has been a continuous decline in the forest cover on Gusii highlands due to an increase in the population density of Abagusii as well as high demand for more farming land beginning 19th century due to the introduction of new crops and farming methods which made farming a more viable economic activity among the Abagusii. Some of the forests were cleared for tea plantations just like neighbouring Kericho and Bomet counties of today. The Abagusii were originally organized into family units analogous to clans/tribes which were also further organized into sub-clans/sub-tribes. The major Abagusii clans/tribes include Abagetutu, Ababasi, Abanyaribari, Abamachoge, Abanchari, and Abagirango with their respective sub-clans/tribes. However, during the 19 century with the introduction of maize, tea and coffee as well as several other crops initially absent on the Continent of Africa, the Abagusii now largely practise crop cultivation alongside keeping animals despite originally being predominantly pastoralists. Most of the crops originating outside Africa such as bananas/plantains, maize, tea, coffee, rice and several other crops were originally introduced to the African coastlines especially the eastern coastline by the Arab, Portuguese, Indian and Southeast Asian traders as well as the western and southern coastlines of Africa through the Dutch, Portuguese and Spanish traders. These crops were later introduced to the interior of Africa during the 19 century by the European colonists who cultivated these crops in various African countries that they colonized. These crops were later inherited by the indigenous African peoples in post-colonial Africa that learnt the cultivation of these foreign crops from the European colonists through labour on white farms.

The Abagusii people today

The Abagusii is regarded as one of the most economically active communities in Kenya, with rolling tea estates, coffee, and banana groves. However, the Kisii district has a very high population density. It is one of the most densely populated areas in Kenya (after the two cities of Nairobi and Mombasa), and the most densely populated rural area. It also has one of the highest fertility and population growth rates in Kenya (as evidenced by successive census and demographic surveys). In fact, the fertility rate of Kisii ranks among the highest in the world. These factors have ensured the Abagusii to be among the most geographically widespread communities in East Africa. A disproportionately large number of Abagusii have gone abroad in search of education. The Abagusii are some of the most heavily represented Kenyans in foreign (usually Indian and American) universities and a few in the United Kingdom. Their lands are currently overpopulated despite their rolling fertile hills, spurring immigration to other cities in Kenya and a substantial representation in the United States, especially in major hub cities like Houston, Atlanta, Jersey City, Dallas, Cleveland and Minneapolis-Saint Paul. The hard cash that flows from the diaspora has spawned significant economic prosperity in a locale lacking in politically motivated ‘hand-me-downs.

The Abagusii people have as a result moved out of their two counties and can be found virtually in any part of Kenya and beyond. In Nairobi, Mombasa, Nakuru, Eldoret, Kisumu and many other towns in Kenya, they run most businesses. For example, the “matatu” business in Nairobi estates like Utawala, kawangware, Dandora, Embakasi, Kitengela, Matasia, etc. They have bought land and are residents in most of these Nairobi estates like Utawala, Ruai, Joska, Kamulu, Kitengela, Rongai, Ngong, etc. They are generally, by nature, independent and thorough in their pursuits whether in education, professional practices, or even religious belief(Islam, Christianity or Traditional African religions); making them more visible than their absolute numbers. The Abagusii people are very diverse in terms of culture, religion and appearance(ranging from caucasoid to negroid-like features). Abagusii people are not related to the Kissi people of West Africa or to the Kisi people of Malawi.

Genetics

There have not been any extensive genetic studies conducted to determine the ethnogenesis of the Abagusii people. Realistically and historically speaking, the Abagusii are genetically related to the Maasai, Kipsigis, Luo, Kuria, and Meru as well as the Omotics, Eastern Cushites, Southern Cushites and Ogiek. In fact, the Maasai and Kipsigis are genetically cousins to Abagusii and the Meru and Kuria are sister tribes to the Abagusii. From the historical point of view, the present-day Gusiiland as well as much of former Nyanza and Rift Valley provinces as well as the rest of Kenya were originally inhabited by ancient agro-pastoralists and hunters/gatherers that are the Nyanza/Rift Cushites aka Sirikwa/Loikop. These ancient agro-pastoralists and hunters/gatherers were of the same stock as the ancestors of the modern Cushites, Omotics, Nilotes, as well as Ogiek and, are believed to have contributed to the ancestry of the modern Abagusii people. These ancient agro-pastoralists and hunters/gatherers are indeed the original ancestral population from which the Abagusii people emerged and are the progenitors of all the major Abagusii clans namely, Abagetutu, Abanyaribari, Abamachoge, Abagirango, Ababasi, and Abanchari. These ancient agro-pastoralists and hunters/gatherers are believed to have migrated from Misiri, the semi-mythical homeland of Abagusii in the North of Mt. Elgon and are the source of the Abagusii oral literature, language and culture. These agro-pastoralists and hunters/gatherers from the North are the original and founders of the Abagusii people and were later joined by a later group of Abagusii from the West of Lake Victoria and from the South. The later group of Abagusii from the West of Lake Victoria were assimilated from the Olusuba speaking Suba people (Kenya) that migrated to Kenya from Buganda and Busoga in the 1800s. However, there is a lack of evidence of migration from the South. The later group of Abagusii from the West of Lake Victoria and south are a minority of the Abagusii population and were later additions to the original Abagusii that were the ancient agro-pastoralists and hunters/gatherers from the North of Mt. Elgon. Based upon those historical facts, the majority of the Abagusii are realistically mostly genetically similar to the Cushites and Nilotes by over 80 per cent and least genetically similar to the Bantu speakers. Clear evidence of this claim is demonstrated by the physical appearance of the majority of Abagusii which is more similar to the Nilotes and Cushites and less similar to the Bantu speakers. Indeed, the majority of Abagusii are not typical Bantu speakers in terms of culture, appearance and language. In fact, some studies on East African Bantu languages show that Ekegusii, Kuria, Ngurimi, Simbiti/Egesuba, Rangi and Mbugwe languages are structurally different from typical Bantu and more similar to the Cushitic and Nilotic languages. This suggests that the Abagusii together with Kuria, Ngurimi, Rangi, Mbugwe and the Simbiti originated from an ancestral population of the same stock as the ancestors of the modern Cushites, Nilotes, Omotic and Ogiek. The Abagusii and the mentioned related tribes were most likely originally non-Bantu people that got Bantunized through intermarriage and interaction with Bantu speakers which explains why their respective languages are more similar with the Nilotic and Cushitic languages structurally and intense aspect and only some lexical similarities with the Bantu languages. The major conclusion that can be made here is that most of the so-called Bantu languages and cultures originated from a pre-existing neolithic agro-pastoralists from the North and have been acquired by the so-called Bantu people through interaction and assimilation with the pre-existing agro-pastoralist population of Eastern Africa. Indeed, the mentioned tribes occupy areas that have been historically inhabited by the ancient agro-pastoralists and hunters/gatherers of the same stock of the ancestors of the modern-day Cushites, Nilotes, Omotic and Ogiek. However, some of the Abagusii will be genetically similar to the Bantu speakers particularly those that were assimilated from the Olusuba speaking Suba people (Kenya) and Luhya, which are a minority of the Abagusii population.

Relationship with Nilotic and Cushitic speakers

The division of indigenous African peoples into; Nilotic, Bantu, Niger-Congo, Cushitic, Sudanic, West Sudanic (West Africans), Nilo-Saharan, Afro-Asiatic, Chadic and Khoisan linguistic groups was a purely European concept that never existed in pre-colonial Africa. These linguistic classifications began in the 1900s with Joseph Greenberg and other European scholars and conquerors pioneering the idea of dividing Africa into different linguistic groups. The creation of all these linguistic groups made colonization of Africa easier as Africa was divided into regions based on the created linguistic groups. For instance, Southern African was defined as a Khoisan area, Eastern Africa as a Cushitic area, Central Africa (and sometimes West Africa) as a Bantu area, Sahelian region and Nile valley as a Nilo-Saharan area and West Africa as a West Sudanic area. After the creation of all these linguistic groups, collective histories for each group were created that assumed the common origin of each linguistic group. For example, the Nilotic speaking communities were assumed to be from South Sudan, the Cushitic speaking communities were assumed to be from Ethiopia and the Bantu speaking communities were assumed to be from the border of Nigeria and Cameroon. These linguistic groups were also associated with specific economic activities regardless of what they practised. For instance, the Cushitic and Nilotic speaking communities were assumed to be all herders, and the Bantu speaking communities were assumed to be all farmers. Each of these linguistic groups was assumed to be all genetically homogeneous and DNA haplogroups such as E1b1a, E1b1b, B-M60, A3 and A1b1 were created for each group. The haplogroup E1b1a was associated with Bantu, E1b1b with Cushitic speakers, B-M60, A3, and A1b1 were all associated with Khoisan, Nilotic speakers and pygmies. This contributed to tribes that were originally unconnected developing a sense of unity and belonging together. All these groups were polarized against each other depending on region and ethnic groups hence some of the conflicts and bitter relations witnessed today between different linguistic groups. The creation of these linguistic groups is one of the major contributing factors to the blanket stereotypes created against each of these linguistic groups in modern African societies. In the context of Kenya, the Abagusii relationship with the neighbouring Nilotic speaking communities such as Maasai people, Nandi people, Kipsigis people and Luo people has always been painted as negative on social media and in public opinions of some people especially scholars and researchers. The Nilotic speaking communities have been stereotyped as hostile and warlike compared to the Abagusii people and the Bantu speaking African tribes in general. Despite these public opinions, the Abagusii indeed have had good relationships with the neighbouring Nilotic speaking communities who have always been their neighbours for many years prior to the colonization of Africa. Prior to colonization, the Abagusii engaged in barter trade with these communities especially the Luo people and at times worked together during cattle raids to defeat the raiders. For instance, the Abagusii together with Luo and Maasai worked together to defeat the Kipsigis cattle raiders.

The Abagusii and Maasai also lived side by side around Kericho for many years before the Abagusii migration to their current homeland of Gusii highlands. The co-existence between the Abagusii and the neighbouring Nilotic communities was largely peaceful despite these communities and Abagusii occasionally engaging in cattle rustling activities which were sometimes violent. The cattle rustling and raiding were mainly common among the Maasai people and to a lesser extent the Kalenjin people who believed that cattle were given to them by God to control and take care of them. The Abagusii have more in common with the Nilotic speaking communities in terms of culture as well as migration and settlement patterns compared to the Bantu speaking communities. For instance, the Abagusii were originally predominantly herders in pre-colonial Africa and farmers to a lesser extent which is very similar to the Nilotic communities. The migration routes and settlement patterns of Abagusii in present-day Kenya are very similar to those of the Kalenjin people, Ateker people including the Maasai people and Luo people. For instance, the original point of dispersal to other regions of Kenya was Mt. Elgon for the Abagusii, Kalenjin people, Luo people and Ateker people. A number of clans of the neighbouring Nilotic communities especially the Kipsigis have Abagusii origins suggesting a very close relationship between Abagusii and neighbouring Nilotic speaking communities. In terms of relationship with the Cushitic communities, the Abagusii don’t live in close proximity with the Cushitic speaking communities that are mostly found in geographical Eastern and Northern Kenya. However, there is a similarity between the Abagusii cultures and cultures of some Cushitic communities particularly the East Cushitic communities such as Konso people and Oromo people. For instance, a majority of the Cushitic communities are herders which were originally dominant among Abagusii though still practised to a lesser extent. The oral literature of Abagusii indicates migration from Misiri that lies to the North of Mt. Elgon prior to settlement at the Mt. Elgon region of Kenya. This pre-Elgon homeland of Abagusii is the Nile Valley region adjacent to modern Ethiopia thus the many similarities between Abagusii and the Nilotic and Cushitic speaking communities. The general conclusion is that the Abagusii have more in common with the Cushitic and Nilotic communities than with the Bantu speaking communities in several aspects. These similarities suggest that Abagusii share origins with some Cushitic and Nilotic communities. On the basis of the Abagusii history and migration routes, they could be more genetically related to some Nilotic and Cushitic speaking communities than they are related to the Bantu speaking communities. Indeed, a majority of Abagusii share physical appearance with some Cushitic and Nilotic speaking communities as well as with some closely related Bantu speaking communities such as the Abakuria. For instance, an outsider will confuse a majority of Abagusii with the Cushitic speaking communities, Nilotic speakers and so being confused for some other closely related Bantu speaking communities. Generally speaking, the majority of Abagusii don’t possess the very prominent facial features that tend to be common in some Bantu speaking communities as well as some other linguistic groups in Central, Western, Eastern and Southern Africa.

Relationship with East Africa Bantu speakers

During the pre-colonial period, the Abagusii mostly had contact with the Luo, Nandi, Kipsigis and Maasai who have always been their immediate neighbours as well as other tribes in the Lake Victoria region of East Africa. The Abagusii Engaged in Barter Trade with some of these communities such as Luo, Nandi, Kipsigis and Maasai as well as other Lake Victoria communities depending on proximity. The Abagusii had very limited contact with the Bantu speaking communities and led very independent and distinct lifestyles from a majority of the Bantu communities of East Africa and possibly the entire continent of Africa. Indeed, even the Ekegusii language is significantly different from most East African as well as other Bantu languages of Africa in some structural elements. This supports the view that Abagusii were originally separate from other East African Bantu tribes as well as the Bantu language group as a whole. This is despite being linguistically classified as Bantu since the 1900s. In the context of Kenya, the Abagusii originally never had contact with the Bantu speaking communities in the former Central, Eastern and Coast provinces of Kenya. This is with the exception of Ameru that migrated to the former Upper Eastern province from present-day Gusiiland and indeed the Kimiiru is very similar to Ekegusii. The only other Bantu speakers in contact with the Abagusii in pre-colonial Kenya include the Kuria, Zanaki, Ikoma, Ngurimi, Rangi, Mbugwe and Simbiti tribes which migrated to their current lands from present-day Gusiiland. This is the clear explanation of why the cultures, as well as the languages, are spoken by the mentioned tribes, and are very similar to Ekegusii. However, in the post-colonial period with the availability of modern transportation, the Abagusii have been able to contact the Bantu speaking communities in Central, Eastern and coastal provinces of Kenya with whom they originally had no contact. The Abagusii have also been able to learn of other Bantu communities they never knew before such as those far away from the lake region of Tanzania, Uganda and other African countries through modern Education on African linguistic groups such as Niger-Congo. A majority of the tribes now labelled Bantu barely knew each other during the pre-colonial period as they were originally very scattered and didn’t have the concept of the term Bantu as a linguistic marker denoting hundreds of diverse tribes in Central, Eastern, and Southern Africa. In the pre-colonial period the term Abantu (The term Abantu is a Nguni term and has distinct versions in other Bantu languages) out of which the term Bantu was coined, was only used to mean people with no Bantu as a linguistic group in mind. The tribes now labelled as Bantu never had a sense of unity or belonging together during the pre-colonial period as they were very scattered and led very distinct and independent lifestyles having no knowledge of each other.

Etymology of Bantu and relevance to Abagusii

The term “Bantu” originates from the Nguni languages of Southern Africa from the term “Abantu” which means people and was coined by Wilhelm Bleek in the 1850s. The term was originally and initially used in South Africa during the apartheid rule to refer to non-Khoisan South Africans and was later used as a linguistic marker denoting hundreds or thousands of unrelated tribes in Central, Eastern and Southern Africa. The term “Bantu” has no grammatical meaning in the Nguni languages out of which it was coined. The singular form of the word Abantu is Umuntu which renders the term Bantu meaningless as it makes no grammatical sense. The term Bantu as well as the so-called Bantu speakers did not exist in precolonial Africa. Prior to the colonization of Africa, the term “Abantu” as well as its other distinct versions in other so-called Bantu languages was used to simply mean people and nothing more than just that. However, beginning 1900s with the classification of indigenous African peoples into; Bantu, Niger-Congo, Nilotes, Nilo-Saharan, Sudanic, West Sudanic(West Africans), Cushites, Afro-Asiatic, Hamites, and Khoisan, the term Bantu started being used in reference to tribes that occupy Central, Eastern and Southern Africa. These thousands of tribes were assumed to be the same and having a common origin on the basis of using words similar to Abantu in reference to people. The languages spoken by these tribes were also assumed to be the same and having a common origin on the basis of possessing words similar to Abantu. The assumption that these very diverse and unconnected tribes share a common origin on the basis of the terms similar to Abantu contributed to them being lumped up together into one collective group called Bantu. The assumption that the Bantu languages are the same is not necessarily right given that these languages have very minimal structural similarities and lack mutual intelligibility. The speakers of these languages don’t understand each other and were originally unconnected to each other. In precolonial Africa, these tribes barely knew each other and were very scattered with very little to no contact with each other. These tribes also never had a sense of unity or belonging together and led very independent and distinct lifestyles with no prior knowledge of each other.

After the creation of the Bantu linguistic group, a collective history was coined that assumed that all these thousands of tribes originated at the border of Nigeria and Cameroon and expanded from there to other parts of Africa where they are found. The assumption that these very diverse tribes that were originally very scattered and disunited expanded together from the border of Nigeria and Cameroon is rather absurd. This raises the question of when these originally unconnected tribes learnt about each other and decided to expand together from the border of Nigeria and Cameroon where they are absent. This leads to the conclusion that the so-called Bantu expansion never occurred and the expansion was just used to justify land dispossession from the black South Africans during apartheid as well as other Africans during the colonial period. The assumption that thousands of the so-called Bantu speaking tribes expanded from the border of Nigeria and Cameroon and are genetically and linguistically homogeneous is rather absurd and inaccurate. The Bantu speaking tribes are in fact the most diverse in Africa in terms of genetics, culture, appearance, origins, history and linguistics. The general assumption that belonging to the Bantu linguistic group automatically makes people genetically related is also quite absurd as these thousands of tribes lack a common origin and were randomly labelled Bantu on the basis of the simple term Abantu. Speaking a Bantu language does not necessarily mean that one cannot be related to people from other linguistic groups given that all these groups were also randomly lumped up together. For instance, the Bantu speaking tribes in Southern Africa are genetically more related to Khoisan than they are related to East African Bantu tribes and other regions. The Bantu speaking tribes in East Africa especially Kenya are also genetically more related to the Nilotic and Cushitic speaking communities than to the Central African Bantu speaking tribes that are also more related to Southern African Bantu speaking communities. Therefore, the term Bantu has no genetic meaning other than just being a linguistic marker of several thousand unrelated tribes. The over 600 Bantu languages are distinct from each other enough to be treated as distinct languages that don’t belong to one collective linguistic group. In terms of importance, the term Bantu only has meaning to the Nguni languages out of which it was coined as well as other tribes with the exact spellings of the term “Abantu”. The term is of no meaning and importance to Abagusii as it is a mere linguistic marker and not a genetic marker of several diverse African tribes.

Origins of Agricultural Practices in Gusiiland

The agricultural practices of the Abagusii originate from the Neolithic Agropastoralist inhabitants of present-day Gusiiland and much of Luo-Nyanza and the former Rift Valley provinces as well as the rest of Kenya. The original crops grown in Gusiiland were mainly cereals such as millet, sorghum and barley as well as a pumpkin all of which originate from the ancient Agro Pastoralist ancestors of the modern Abagusii as well as the Kuria, and the Luo of Kenya and Northern Tanzania. Most of the other crops grown today in Gusiiland such as tea, coffee, bananas/plantains and several others have been grown in Gusiiland since the 19th century after their introduction by the British. For instance, by the 1920s maize had been introduced to Gusiiland and had overtaken finger millet and sorghum as staple crops and cash crops which ensured that maize became the new dominant staple crop. Coffee and tea as well as several other exotic crops grown in Gusiiland today were introduced during the same time period as maize. Most of the crops originating outside Africa such as bananas/plantains, maize, tea, coffee, rice and several other crops were originally introduced to the African coastlines especially the eastern coastline by the Arabs, Portuguese, Indian and Southeast Asian traders as well as the western and southern coastlines of Africa through the Dutch, Portuguese and Spanish traders. These crops were later introduced to the interior of Africa during the 19 century by the European colonists who cultivated these crops in various African countries that they colonized. These crops were later inherited by the indigenous African peoples in post-colonial Africa that learnt the cultivation of these foreign crops from the European colonists through labour on white farms. It is important to note that the Abagusii were mainly pastoralists and hunters/gatherers during pre-colonial Kenya and practised cereal and pumpkin farming to a lesser extent.

Abagusii economic activities

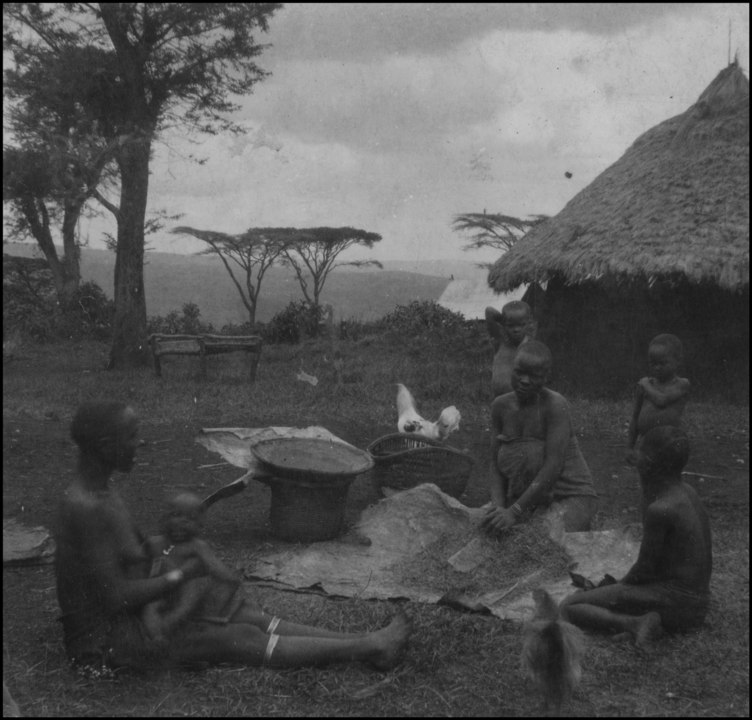

Gusii women grinding millet while other natives watch ca.1916-1938

Gusii women thrashing corn with children watching ca.1916-1938.

Gusii women grinding millet ca.1916-1938

Subsistence agriculture and herding

During the pre-colonial period, the Abagusii cultivated finger millet, sorghum, and root crops as well as other local crops. By the 1920s with the introduction of maize to Gusiiland, finger millet and sorghum were largely replaced by maize as a staple and cash crop. Other crops cultivated by Abagusii today include cassava, potatoes, tomatoes, bananas, beans, onions, tropical fruits and peas as well as several other crops. By the 1930s, coffee and tea had reached Gusiiland and were being cultivated as major cash crops. During the pre-colonial period as well as the early colonial period, the Ox-drawn plows and iron hoes were used in the cultivation of crops. Today the same cultivation tools are used alongside modern cultivation tools. During the pre-colonial period, the Abagusii were predominantly herders that kept cattle, goats and sheep as well as kept poultry. Today, the Abagusii still keep livestock and poultry alongside farming. The high population density of Abagusii has contributed to the utilization of available land for agriculture to satisfy subsistence and commercial needs thus making farming a dominant activity. In addition to agriculture, the Abagusii also carry out business activities in major towns and cities in Kenya and abroad. The Abagusii also participate in white-collar jobs in Kenya and abroad.

Industrial activities

During the pre-colonial period, Abagusii produced iron tools, weapons, decorations, wooden implements, and baskets for diverse uses. The Abagusii also made pottery products such as pots and imported some from the neighbouring Luo community. The most respected and highly valued activity was the smelting of iron ore and the manufacture of iron tools. The blacksmiths were highly respected, wealthy and influential members of Abagusii society, but did not form a special caste as the Abagusii society was not based on caste stratifications. Smithing activities were mainly carried out by men.

Trade

The form of trade carried out on pre-colonial Gusiiland was barter trade and mostly took place within homesteads as well as with neighbouring communities especially the Luo people. The major products exchanged included tools, weapons, crafts, livestock, and agricultural products. The cattle served as a form of currency among Abagusii for the products exchanged and goats were used as a currency for lower-valued products. The barter trade between Abagusii and Luo took place at border markets and at Abagusii farms and was mainly carried out by women. Today with the advent of the modern concept of trade, the Abagusii have established shopping centres, shops and markets which have connected them with other regions of Kenya besides the neighbouring communities. These markets are increasing exponentially and the Abagusii are getting more and more connected to the rest of Kenya as opposed to the pre-colonial Kenya where they only had contact with neighbouring communities.

Division of labour

In the traditional Abagusii society, labour was divided between males and females. The women-specific duties included cooking, crop cultivation and processing, fetching water and firewood, brewing, and cleaning while the men’s specific duties included herding, building houses and fences, and clearing cultivation fields, and other duties. Men were also involved in crop cultivation but with fewer responsibilities than women. Herding was primarily carried out by boys and unmarried men in the grazing fields and girls and unmarried young women helped with crop cultivation. Today the division of labour between males and females has significantly changed and is now disadvantageous to women as they perform most of the duties traditionally meant for men. There is no longer equal distribution of labour between men and women as it was traditionally.

Language

They speak the Ekegusii (also called omonwa Bwekegusii). However, some older texts refer to this community as Kosova. Studies on East African Bantu have found the Ekegusii together with the Kuria, Simbiti/Egesuba, Ngurimi, Rangi, and Mbugwe languages to be very distinct from the typical Bantu languages in terms of structure and tense-aspect. These languages only have some lexical similarities with other Bantu including the Great Lakes Bantu languages in the case of the Ekegusii, Kuria and Simbiti/Egesuba, but are far distinct from these languages. These languages have been found to be more similar to the Nilotic and Cushitic languages in several structural and tense aspects. This raises debate as to whether the Abagusii, Kuria, Ngurimi, Simbiti, Rangi and Mbugwe tribes should be included in the Bantu language group given that their respective languages differ greatly from typical Bantu languages. These six tribes should indeed be treated as independent/isolated or even assigned a separate language family rather than being lumped into the Bantu language group where they clearly don’t belong.

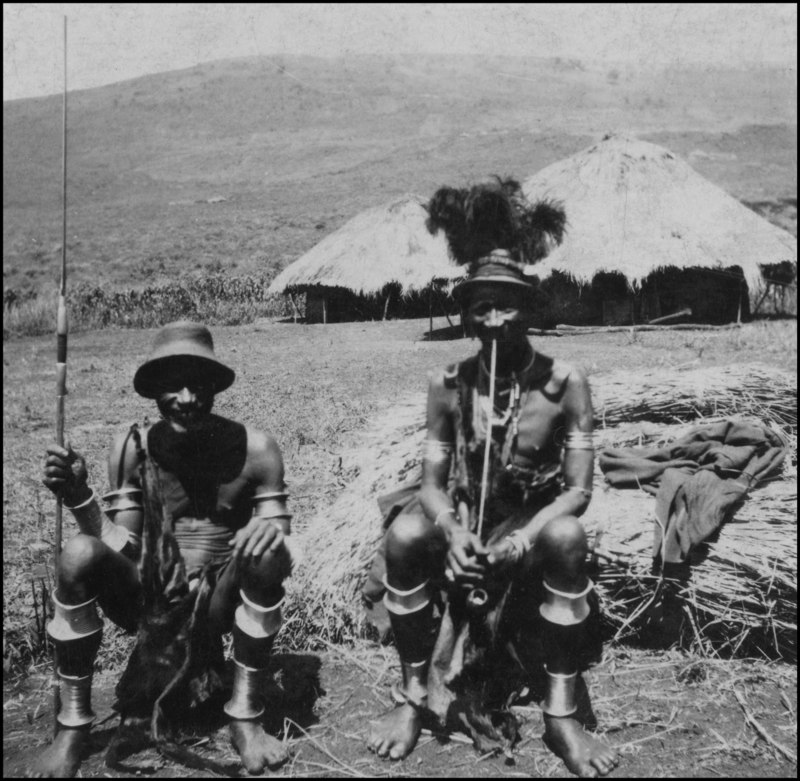

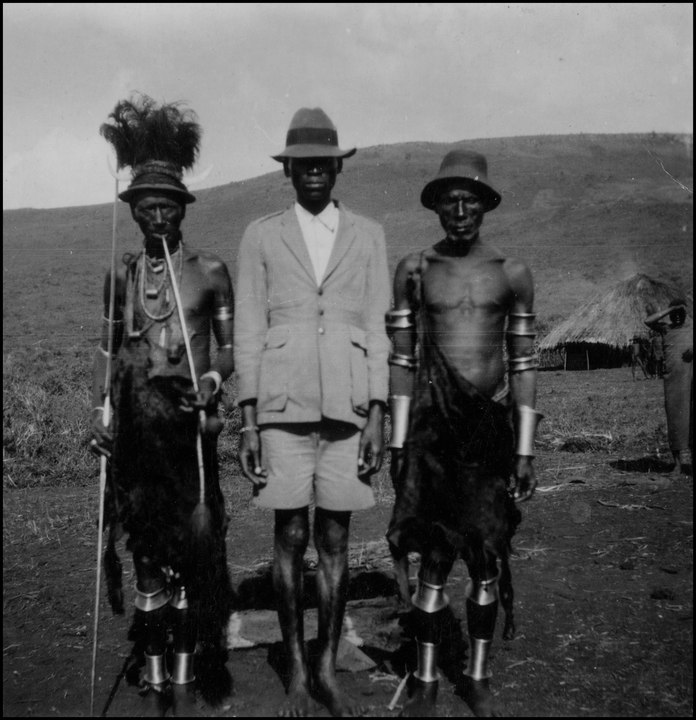

Culture

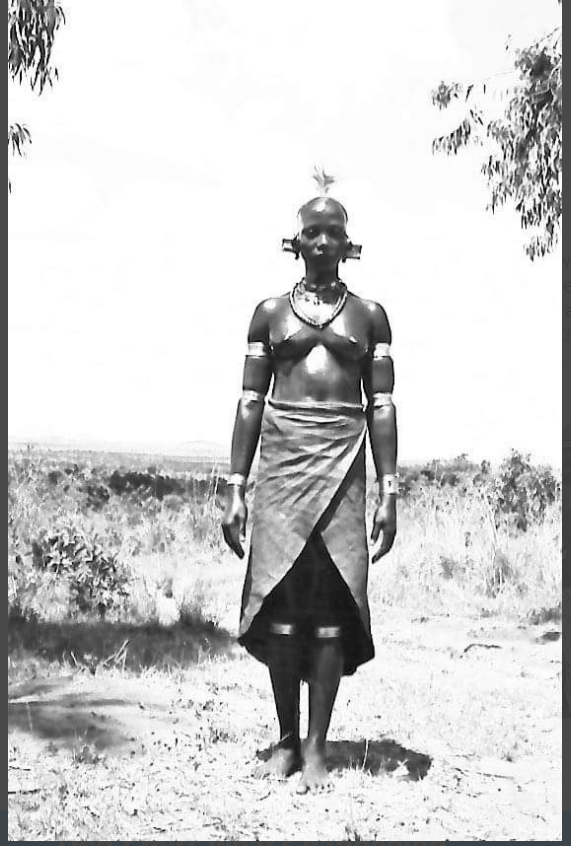

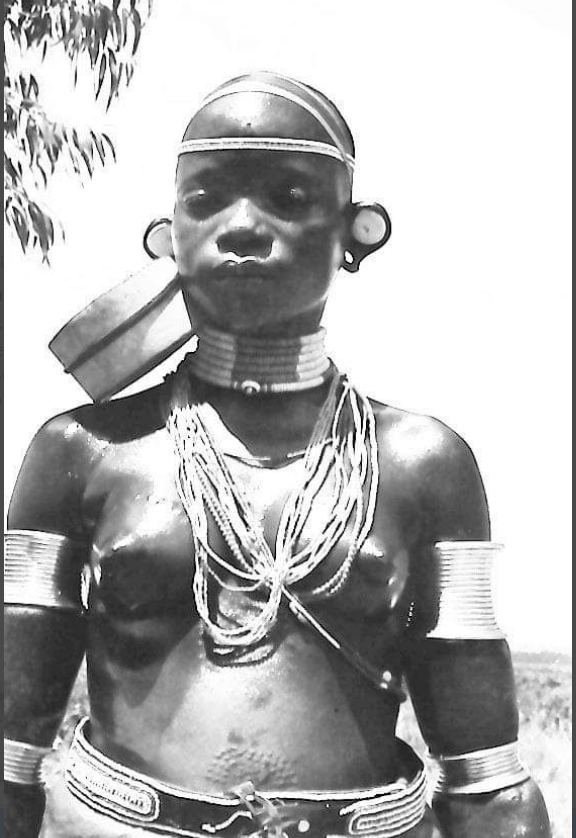

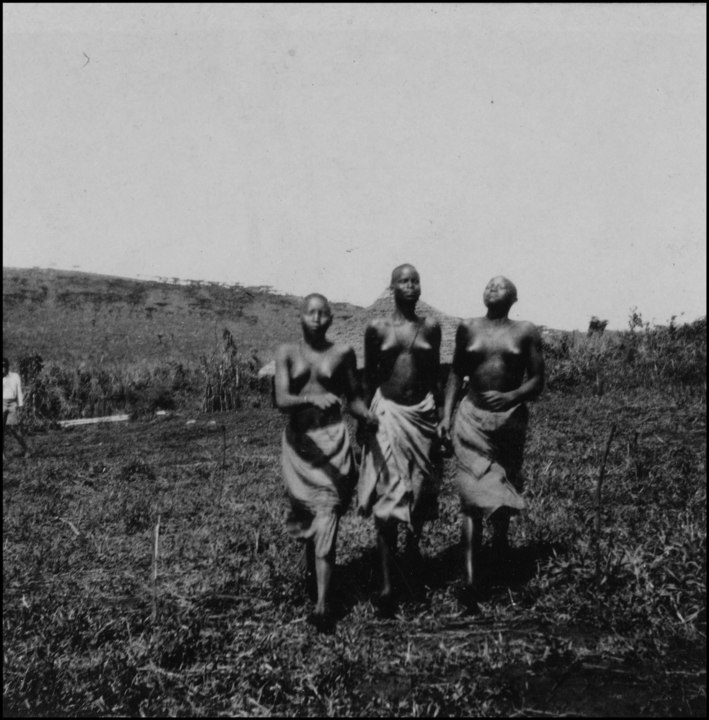

A Gusii woman with a baby and a load of firewood ca.1916-1938

A Gusii woman sitting in front of a hut ca.1916-1938

The Abagusii play a large bass lyre called obokano. Drums and other musical instruments like flutes were also used. They are also known for their world-famous soapstone sculptures “chigware” mostly concentrated in the southern parts of Kisii County around Tabaka town. Circumcision of boys at around the age of ten as a rite of passage without anaesthesia is common among the Abagusii. Abagusii does not marry or marry into tribes that do not circumcise although culture has been eroded and the later generations may not consider this. Girls also underwent clitoridectomy as a form of circumcision at an earlier age than boys. This ritual takes place annually in the months of November and December followed by a period of seclusion during which the boys are led in different activities by older boys and girls are led by older girls, and is a great time of celebration indeed for families and communities at large. Family, friends and neighbours are invited days in advance by candidates to join the family. During this period of seclusion, only older circumcised boys and girls are allowed to visit the secluded initiates and any other visitor could cause a taboo. It’s during this period that initiates were taught their roles as young men in the community and the do’s and the don’ts of a circumcised man. The initiated boys and girls were also taught the rules of shame (“Chinsoni”) and respect (“Ogosika”). Unlike most communities in Kenya where the circumcised boys and/or girls joined an age set or age group, the circumcised Gusii boys and girls did not join an age set or age group given that the Abagusii lack age sets and age groups.

Some of the notable musicians from the Abagusii community include Nyashinski, Rajiv Okemwa Raj, Ringtone, Mwalimu Arisi O’sababu, Christopher Monyoncho, Sungusia, Riakimai ’91 Jazz, Embarambamba, Bonyakoni Kirwanda junior band, Mr Ong’eng’o, Grandmaster Masese, Deepac Braxx (The Heavyweight Mc), Jiggy, Mr. Bloom, Virusi, Babu Gee, Brax Rnb, Sabby Okengo, Machoge One Jazz, among others.

Political organization

A depiction of a typical traditional Gusii parliament ca.1916-1938.